I am sure you have heard this one; Victorian doctors invented the vibrator to masturbate women to 'hysterical paroxysm' (orgasm) because they had been hand cranking so many of their patients, to cure them of their hysteria, that they developed repetitive strain injuries. We love this story. I love this story. Hollywood loved this story so much that the 2011 film, Hysteria, was based entirely on this story. So it is with a heavy heart that I have to tell you, this really is just a story. Like ‘trickle down’ economics and Jamie Lee’s hermaphroditism, it’s an urban myth. But, like all the best stories, there are flashes of truth in it. I will tread lightly and salvage as much as I can because I know how pervasive and popular this myth is. Not only is it much loved, it's well established and is referenced in numerous texts, documentaries, online sources and has become part of our collective history. We love it because it goes straight to the hysterical heart of the Victorian sexual hypocrisy that we enjoy rolling our eyes at; ‘did you know Victorian doctors were diddling female patients, but considered exposed table legs to be sexually obscene? So glad we’re not like that now!’ (Except the table legs thing is also myth, but that’s another post for another day.)

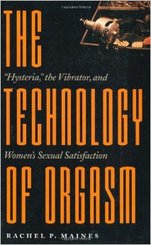

The root of the minky massage theory is Rachel Maine’s book, The Technology of Orgasm (1999). Here, Maines hypotheses that doctors masturbated women to orgasm for health reasons, and that the vibrator was nothing short of a ‘God send’ for the physicians suffering from repetitive strain injury in their index fingers. More than this, Maines makes the case that this practice can be traced back to Classical times. However, it has to be said that her evidence for medical vulva massage in the ancient World has been discredited, most notably by Professor Helen King, who took apart such claims in the academic equivalent of a Vulcan death grip, which you can read here. It’s also important to remember that Maines herself refers to her argument as a hypothesis; and to be fair, it’s a damn interesting one. In an online interview in 2010, Maine said,

‘People just loved my hypothesis and that’s all it is really, it’s a hypothesis, that women were treated with massage for this disease, hysteria, which has supposedly existed since the time of Hippocrates, 450 B.C., and that the vibrator was invented to treat this disease. Well, people just thought this was such a cool idea that people believe it, that it’s like a fact. And I’m like, ‘It’s a hypothesis! It’s a hypothesis!’. But it doesn’t matter, you know? People like it so much they don’t want to hear any doubts about it’ (Maines, 2011).

So, let’s unpack this hypothesis a little further. Make no mistake, Victorian doctors were obsessed with sex and health, and there were some highly questionable medical theories flying around; from Dr Kellogg’s thoughts that masturbation was terminal, to Italian criminal anthropologist, Cesare Lombroso’s theories that sex workers had no sensation in their clitorises, as they had been rendered ‘insensible’ through ‘overuse’ (Lombroso et al., 2009). But the theory that Doctors invented vibrators to butter the whisker biscuit and cure hysteria is doubtful for a number of reasons.

Joseph Mortimer Granville Joseph Mortimer Granville

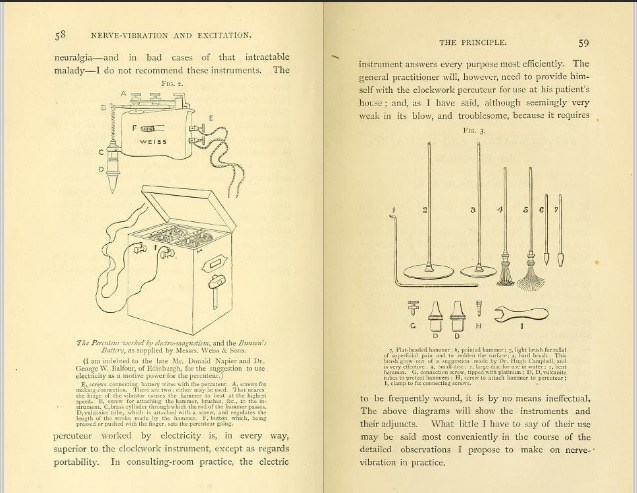

British doctor, Joseph Mortimer Granville, patented the first electrical vibrator in the 1880s, not as a sexual device but as a massager to relief the aches and pains of men – NOT women; he was quite clear on that. His invention was known as the 'Granville Hammer' as it was designed to strike to body in a percussive motion. In his book Nerve-Vibration and Excitation as Agents in the Treatment of Functional Disorder and Organic Disease (1883), he wrote, "I have never yet percussed a female patient ... I have avoided, and shall continue to avoid the treatment of women by percussion, simply because I do not wish to be hoodwinked, and help to mislead others, by the vagaries of the hysterical state" (Granville, 1883). Furthermore, one look at this contraption and I am sure we can all agree that this electrified hammering device is not something you would want anywhere near your clacker without adult supervision and a safe word. This was not designed for internal use.

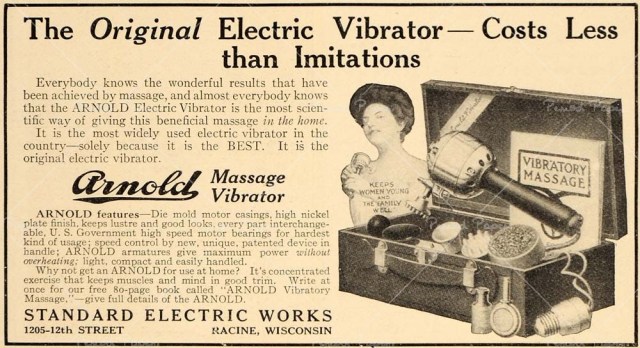

Other vibrating massagers soon followed suit on a wave of pseudo-scientific theories about electricity and vibrating massage, which was touted as a cure all panacea, along with rectal dilators and radium. Vibrating massage promised to alleviate all manner of mental and physical disorders (including the mysterious ‘hysteria), but they were not designed for use on the genitals, and, more importantly for this article, they were not used by Doctors to induce orgasm.

Now, that does not mean that people did not figure out that these massage devices could be put to other, less holistic uses. I like to define a ‘kink minute’ as the insanely short length of time between the introduction of new technology and its adaptation for sexual purposes. And as with the speculum, the nurse’s uniform and Viagra, the vibrator went from medical to mucky in a kink minute. As this early pornographic film, Massages (1930) shows, the vibrator and the massage fantasy have long been saucy. But, you can also see how this device was supposed to be used; and notice, the vibrator is not used internally, but rather on the happy chap’sbottom and thighs, stopping for a few seconds on his penis.

https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Massages.ogv  28,000 year old phallus 28,000 year old phallus

And if we are to believe that vibrators were common knowledge and widely used to induce orgasm, we have to account for the fact that there is not one mention of this in any known Victorian pornography (textual or visual). Not one. However, there are many references to dildos, and occasionally the odd cucumber put to good use. Sex toys are not new. The earliest dildo found was excavated in Germany and is over 28,000 years old. The Victorians knew how to design a good sex toy – the design has (unsurprisingly) changed very little in over 28,000 years. It tends to be, well, cock shaped. Have a look around any modern day sex shop and we can see that the cock shape for a sex toy is still very much in vogue. Victorian dildos were made from wood, leather and even ivory, and they were certainly a lot of fun, as this extract from The Pearl (1880) demonstrates: "As we are five to two you will find I have a stock of fine, soft, firmly made dildoes to make up the deficiency in males, which alternated with the real article will enable us to thoroughly enjoy ourselves" (The Pearl, 1879). Then, there was this jolly song, titled 'The Old Dildo', published in 1880. She flew with the treasure into her room (Its size was the handle of a broom). Oh! what ecstatic moments she passed there, As she threw up her legs on the back of a chair. Through each vein in her body the fire lurked, Surely and quickly the engine worked; Face her, back her, stop her no! no! Faster and faster flew the old Dildoe. Chorus- Oh! the old Dildoe, oh, the old whore's Dildoe (The Pearl, 1880).

Not only is there no known mention of Doctors and vibrators in Victorian pornography, there is also no mention of it in the work of the early and pioneering sexologists. Iwan Bloch, Havelock Ellis, Richard von Kraft-Ebing and Freud meticulously catalogued every fetish, paraphilia and known expression of sexual behaviour, but not one of them mention doctors, vibrators and orgasm. Ellis and Bloch even describe some women deriving sexual pleasure from sewing machines and beetroot, but there is no mention of a vibrator. Fifty years later, in his seminal Behaviour in the Human Female (1953), Alfred Kinsey does not mention vibrators in his lengthy and comprehensive chapters on female masturbation.

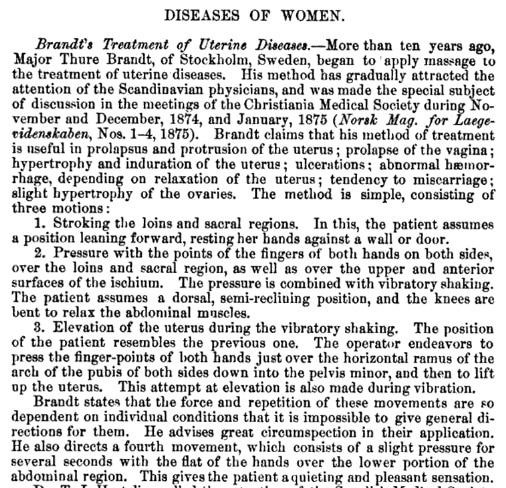

But, what about medical texts themselves? Surely there must be some mention of doctors conducting ‘pelvic massage’ or the 'hysterical paroxysm'? Well, yes! Yes, there is and lots of it. The medical craze for pelvic massage came from the work of Swedish obstetrician and gynaecologist, Thure Brandt Brandt (1819-1895), who began treating women in 1861. The ‘Thure Brandt method’ of pelvic massage and ‘manipulating the womb’ proved very popular. The International Record of Medicine and General Practice Clinics (1876) described the technique in some detail. As you can see, the technique is performed outside the body and with a noticeable lack of a vibrator or an orgasm. "Vibrating" is part of the massage, but it means vigorously shaking the patient whilst applying pressure to the pelvic area with the hands. In 1895, Brandt published The physiotherapy in gynaecology and the mechanical treatment of diseases of the uterus and its appendages by Thure Brandt, which contains possibly the most terrifying illustrations of gynaecological techniques ever produced in the history of humanity.

(Brandt, 1895)

Once you have moved past the fact that the doctor and patient strongly resemble escapees from Area 51, you will notice that the technique is about applying pressure to the pelvic area in a variety of odd positions. We can also see that some of the massage was internal (this was a gynaecological procedure after all!), and involved inserting a finger and applying the other hand on the abdomen and pushing downwards. But, at no point is an orgasm, sexual arousal, or a vibrator required. Brandt published this work almost fifteen years after Granville had patented his "hammer", and there were numerous vibrating massagers available, and yet they do not feature in technique. The theories behind ‘pelvic massage’, and the techniques employed are frankly bizarre, but it should not strike us as odd that gynaecologists would perform internal examinations; doctors carried them out then, just as they do now (though, should an alien should ever approach you and ask you to ‘draw your ankles up and let your knees fall apart’ – run. Run far and run fast). When a medical text is describing pelvic massage - it means massage of the pelvic area (and maybe the odd finger.) However, it seems that it is here, in the confusing practice of pelvic massage and fancy fingering, that the myth about doctors collectively draining the national grid as they buzzed their patients into post orgasmic delirium, developed.

The other persistent part of the medical vibrator story is that of “hysterical paroxysm”; which Maines understands as being ‘the female orgasm under clinical conditions’ (Maines, 1999). But, when we start to investigate the medical texts of the era, a hysterical paroxysm doesn’t sound like any orgasm I’ve ever had. Hysterical and Nervous Affections of Women: Read before the Harveian Society describes a hysterical paroxysm as ‘an uncontrollable attack of alternate sobbing and laughter’ (Anderson, 1853). Andrew Whyte Barclay’s A Manual of Medical Diagnosis (1862), describes it as a ‘fit’ and ‘a simulation of epilepsy’ (Barclay, 1862). John Henry Walsh describes the hysterical paroxysm as beginning with uncontrollable giggling, and lasting ‘for at least an hour, and often for five or six’ (Walsh, 1858); and Dr Henry Beasley noted that ‘flatulent distension of the bowels’ often precedes an attack of hysterical paroxysm (Beasley, 1855). I’m sorry, but a farting, giggling fit that lasts an afternoon, may be a lot of fun, but it is not an orgasm. Medical theories of the time do link this strange phenomenon to a gynaecological issue. Walsh wrote that a ‘copious secretion of pale urine accompanies the disease’ (Walsh, 1858). George Bacon Wood wrote that hysterical paroxysm was ‘apt to be worse around the menstrual period’ (Wood, 1852); and James Copland lists menstruation, amenorrhea and ‘morbid conditions of the ovaries’ as leading causes of the hysterical paroxysm (Copland, 1860). But, this should not be surprising as the word ‘hysteria’ comes from Latin hystericus, meaning "of the womb"; and from the Greek hysterikos, meaning ‘suffering in the womb’.

The mysterious medical phenomena known as hysteria has attracted considerable research in modern scholarship, precisely because no one really knows what it is. The word covers a multitude of psychological and physical ailments and, until Freud’s work, was exclusively a woman’s malady. At the risk of oversimplification, hysteria meant the physical and / or behavioural manifestations of mental distress in women. This could be aggression, fainting, nymphomania, or a farting fit. The theory that the womb caused emotional instability can be traced back to Ancient Greece and the ‘wandering womb’ theory. Aretaeus, a physician contemporary with Galen in the 2nd century AD., describes how the womb moves around the abdomen, causing madness.

"In the middle of the flanks of women lies the womb, a female viscus, closely resembling an animal; for it is moved of itself hither and thither in the flanks, also upwards in a direct line to below the cartilage of the thorax, and also obliquely to the right or to the left, either to the liver or the spleen, and it likewise is subject to prolapsus downwards, and in a word, it is altogether erratic. It delights also in fragrant smells, and advances towards them; and it has an aversion to fetid smells, and flees from them; and, on the whole, the womb is like an animal within an animal" (Aretaeus and Adams, 1856). Personally, my womb has always advanced towards a new car smell, but I digress.

By the nineteenth century, the wandering womb theory had fallen out of favour, though it clearly enjoyed a last hurrah in theories of pelvic massage and womb manipulation. A hysterical paroxysm was simply another ill-defined category of hysteria that can be found in nineteenth-century medical manuals; along with the hysterical coma, hysterical headaches, hysterical excitement, hysterical convulsive affections, and (of course) hysterical flatulence.

But more than this, the Victorians knew what an orgasm was! There was no need to dress it up in euphemistic language. Even a cursory glance at the erotic literature of the time will tell you, the Victorians knew what an orgasm was. ‘I felt her crack deluged with a warm, creamy spend whilst my own juice spurted over her hand and dress in loving sympathy’ (The Pearl, 1879). ‘She came again three times in the next six nights; each time we renewed our mutual joys, with ever increasing voluptuous indulgencies’ (Romance of Lust, 1873). “How many times I made her spend it would be impossible to say’ (Saul, 1881). As Fern Riddell, one of the leading academics in Victorian sexuality, argues ‘Victorian doctors knew exactly what the female orgasm was; in fact, it’s one of the reasons they thought masturbation was a bad idea’ (Riddell, 2014).

Not only did Victorian doctors know what an orgasm was, but nineteenth-century medical theories taught that orgasms were potentially dangerous and needed to be limited. Masturbation in women was thought to cause hysteria, not cure it. In The Generative System and Its Functions in Health and Disease (1883), James George Beaney claimed that a disease ‘associated with, and very often closely depending on, female masturbation is hysteria’ (Beaney, 1883). Gunning S. Bedford wrote that ‘excessive sexual excitement, masturbation, etc., are all so many causes capable of giving rise to this nervous disturbance’ (Bedford, 1869). In 1852, Samuel La'mert drew a clear distinction between hysterical paroxysm and masturbation when he wrote ‘females devoted to libidinous and solitary pollutions, are more particularly exposed to hysterical paroxysm’ (La’mert, 1852). In 1894, Dr A.J. Bloch of New Orleans referred to female masturbation as a "moral leprosy." So dangerous was female masturbation thought to be, that it was cited on numerous patient admission forms to Victorian lunatic asylums. Dr Issac Brown famously pioneered clitoridectomies as a cure for female masturbation. He was widely criticized at the time, but he was allowed to continue and publish his findings in esteemed medical journals. Now, I ask you, does this sound like a group of people likely to prescribe a session of fingerbaiting?

But, it’s not all doom and gloom. Although orgasms were carefully regulated, they were encouraged between husband and wife and a woman’s orgasm was thought to be an aid to conception, as this extract from The Art of Begetting Handsome Children (1860) attests. ‘When the woman shall perceive the efflux of seed to approach, by reason of the tinkling pleasure, she must advertise her husband thereof that at the very same instant or moment he may also yield forth his seed, that by collision, or meeting of the seeds, conception may be made’ (Anon, 1860).

So, what can we salvage from this much loved and widespread myth? Well, we can take some comfort that there are nuggets of truth here. It is true that Victorian doctors were fascinated with the female reproductive system, and, like their medical predecessors, linked madness to the womb. In an attempt to cure hysteria, in all its weird manifestations, they prescribed all manner of kinky sounding treatments; including pelvic massage. They also had some very strange ideas about orgasm and masturbation damaging health and causing hysteria. There was also such a thing as a ‘hysterical paroxysm’, which is described as some kind of giggly, gassy meltdown that can last for hours. It’s also true that vibrating massagers became popular in the late nineteenth century.

But, here is the crucial thing; Victorian doctors may have been manipulating, sedating, institutionalising and pummelling the pussies of their poor farting female patients – but they were not masturbating them to ‘hysterical paroxysm’ with electrical vibrators. I live in hope that one day we will find the evidence that erotic massage was used by doctors, because its such a great story. But, even if that day never comes, we can still comfort ourselves that Victorian ladies were enjoying hysterical farting sessions, dildos aplenty and maybe, just maybe, got fingered by an alien. Sorry to be such a buzzkill. References ANDERSON, W. (1864). [Hysterical and Nervous Affections of Women. Read before the Harveian Society.]. 1st ed. Sherriff & Downing: Sydney. Archive.org. (2017). Full text of "The Romance of Lust A classic Victorian erotic novel". [online] Available at: https://archive.org/stream/theromanceoflust30254gut/30254-8.txt [Accessed 12 Mar. 2017]. Aretaeus, and Adams, F. (1856). The extant works. 1st ed. London: The Sydenham Society. Barclay, A. (2012). A manual of medical diagnosis. 1st ed. [Charleston, S.C.]: Nabu Public Domain Reprints. Beaney, J. (1883). The generative system and its functions in health and disease. 1st ed. Melbourne: George Robertson. Beasley, H. and LUCAS, E. (1907). [The Book of Prescriptions: containing 2900 prescriptions ... English and foreign ... comprising also a compendious history of the Materia Medica, etc.]. 1st ed. London: J. & A. Churchill. Bedford, G. (2010). Clinical lectures on the diseases of women and children. 1st ed. [Place of publication not identified]: Nabu Press. Bloch, I. (2001). Anthropological studies on the strange sexual practises [i.e. practices] of all races and all ages. 1st ed. Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. Brandt, T. (1891). Treatment of the diseases of women. 1st ed. [New York]: [William Wood and Company]. Copland, J. and Lee, C. (1860). A dictionary of practical medicine. 1st ed. New York: Harper. Ellis, H. (2013). Psychology of sex. 1st ed. New Delhi: Manas Publications. GRANVILLE, J. (1883). Nerve-vibration and excitation as agents in the treatment of functional disorder and organic disease. 1st ed. J. & A. Churchill: London. Jentzer, A. and Bourcart, M. (1895). Die Heilgymnastik in der Gynaekologie. 1st ed. Leipzig: J. H. Barth. King, H. (2011). Galen and the widow: towards a history of therapeutic masturbation in ancient gynaecology. Journal on Gender Studies in Antiquity, (1), pp.205–235. Kinsey, A. (n.d.). Sexual behavior in the human female. 1st ed. Krafft-Ebing, R., Rebman, F. and Robinson, V. (1939). Psychopathia sexualis. 1st ed. New York, N.Y.: Pioneer Publications. La'mert, S. (1852). Self\preservation: a medical treatise on the secret infirmities and disorders of the generative organs. 1st ed. London: published by the author, and sold in London by James Gilbert, 49, Paternoster Row; and by all booksellers in the kingdom and colonies: in Paris, by Laroque, 5, Boulevard Montmartre. Lesleyahall.net. (2017). Victorian sex factoids. [online] Available at: http://www.lesleyahall.net/factoids.htm#hysteria [Accessed 12 Mar. 2017]. Lombroso, C., Ferrero, G., Gibson, M. and Rafter, N. (2009). La donna delinquente, la prostituta e la donna normale. 1st ed. [Milano]: Et.al. Maines, R. (2017). The Study That Set the World Abuzz - Video. [online] Big Think. Available at: http://bigthink.com/videos/the-study-that-set-the-world-abuzz [Accessed 12 Mar. 2017]. Maines, R. (n.d.). The Technology of Orgasm. 1st ed. [s.l.]: Johns Hopkins University Press. Riddell, F. (2017). No, no, no! Victorians didn’t invent the vibrator | Fern Riddell. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/nov/10/victorians-invent-vibrator-orgasms-women-doctors-fantasy [Accessed 12 Mar. 2017]. SINS., (1881). The Sins of the Cities of the Plain, etc. 1st ed. London: Privately printed. WALSH, J. (1858). A manual of domestic Medicine and Surgery: with a glossary ... Illustrated, etc. 1st ed. London. Ward, S. (2017). Reports on the Diseases of Women. International Record of Medicine and General Practice Clinics, 23, p.209. Wood, G. (1852). A treatise on the practice of medicine. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo.

Denise Carruthers

3/12/2017 10:25:59 pm

Fantastic read, I nearly split myself in half, laughing.

Ashleigh

5/18/2017 07:13:56 am

Pure brilliance. Very informative...now where's my vibrator? 6/27/2017 09:30:48 pm

As a collector of old vibrators, your writing is very helpful. 12/6/2017 10:19:58 pm

This is a great article although I must day it's a bit disappointing to me that the myth is just that. I always thought the vibrator was invented to treat women's hysteria so doctors wouldn't get RSI. 1/29/2018 04:22:32 pm

Hello, Kate! Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed