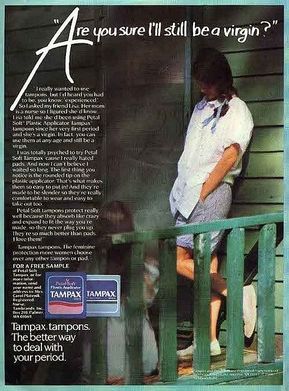

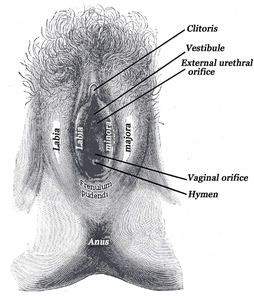

In 2017, researchers at the University of Minnesota published a systematic review of all available, peer reviewed research into the reliability of so called ‘virginity tests’ where the hymen is examined, as well as the impact of said test on the person being examined. The team identified 1269 studies, the evidence was summarised and assessed and this was the conclusion; "This review found that virginity examination, also known as two-finger, hymen, or per-vaginal examination, is not a useful clinical tool, and can be physically, psychologically, and socially devastating to the examinee. From a human rights perspective, virginity testing is a form of gender discrimination, as well as a violation of fundamental rights, and when carried out without consent, a form of sexual assault." (Olson and García-Moreno, 2017) There is no reliable virginity test. So, unlike the virgins in question, we can put that one to bed right away. IT. DOES. NOT. WORK. You can no more prove a virgin by examining their genitals than you can prove a bi-sexual by examining their bellybutton. The only way you can conclusively prove that a woman is not a virgin by examining her genitals is if you look at her vagina and there's a penis in it. That's it: that's the only sure fire way to prove she's not a virgin. However, the fact that virginity cannot be proven, tested, or located on the body has not deterred people from claiming that they can prove it, throughout history. The concept of virginity is undeniably gendered. When anyone is concerned about, or indeed testing, someone's virginity it is almost always the virginity of a girl. Even the word “virgin” comes from the Latin virgo, meaning a girl or a woman who is not married. Men and boys have never been valued by their virgin status in the same way women have. At various points in history, women have been disowned, imprisoned, fined, mutilated, whipped, and even killed as punishment for losing their virginity outside of marriage. Whereas, funny films are made about forty-year-old males.[1] Quite why it is female rather than male virginity that has been so rigorously sanctioned is a matter of some dispute, but it is likely all down to paternal legacies. It’s unfair, but the pre-pill world, pregnancy outside of wedlock was a far more immediate physical and financial concern for the mother than for the father; subsequently it was her shenanigans that were scrutinised rather than his. But more than this, in a paternalistic society where wealth and power are passed down the male line, female chastity is heavily policed to ensure legitimate offspring, and that your worldly goods pass to your children (and not the milkman’s). This theory holds some weight when we consider that in the few matriarchal societies around the world, wealth is passed down the female line. In these culture, female sexuality is regarded very differently.[2]  A protester holds a placard during a protest in New Delhi, on July 29, 2009. © 2009 Reuters A protester holds a placard during a protest in New Delhi, on July 29, 2009. © 2009 Reuters The virgin seal is still highly prized today and has led to numerous damaging rituals around keeping and proving a woman’s sexual purity. Virginity tests are still widespread around the world. These tests usually involve searching for an ‘intact’ hymen, or what’s known as the ‘two finger test’, which checks for vaginal tightness (all highly scientific). Countries where this practice has been reported include Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Palestine, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Turkey, and Uganda (Olson and García-Moreno, 2017). The FGM National Clinic Group state that female genital mutilation is valued ‘as a means of preserving a girl’s virginity until marriage, (for example in Sudan, Egypt, and Somalia). In most of these countries FGM is a pre-requisite to marriage and marriage is vital to a woman’s social and economic survival’ (Fgmnationalgroup.org, 2017). The World Health Organisation estimates that 200 million girls globally have been subjected to female genital mutilation, in no small part to preserve their virginities until marriage (World Health Organization, 2017). The idea of female sexuality purity being a prerequisite for marriage, or that virginity somehow signals a woman's moral character, underpins many cultures and religions around the world. So called ‘Purity Balls’ are held all over America, where fathers take their teenage daughters on a ‘date’, and she pledges to stay a virgin until marriage and he, in turn, pledges to protect his daughter’s virginity until she is married (presumably by guarding her vagina with a shotgun and installing some kind of alarm system). Women can now pay to have their hymens rebuilt for the marriage market, and the hymenoplasty business is booming. Last year a South African KwaZulu-Natal municipality introduced an academic bursary for young women who can prove that they are virgins. And only last month, the Russian Investigative Committee and the health minister, Vladimir Shuldyakov, caused outrage by ordering doctors to carry out ‘virginity tests’ on schoolgirls and to report any found without a hymen to the authorities.  Not only is virginity impossible to prove, it’s also quite difficult to define. We might think that virginity is a very simple thing to define, but it doesn’t hold together all that well when we start to interrogate it a little. What counts as sex for the first time can be more complicated than we might initially think. If two girls have sex, does that count as losing virginity? What if they used a strap-on? If a heterosexual couple hit first, second and third base, but strike out at forth in sweaty, satisfied mess, are they still virgins? Can you lose it to yourself when you discover masturbation? Does it have to involve penile / vaginal penetration? If so, does that preclude LGBTQ sex? Is gay pride really a mass virgin rally? How about if a heterosexual couple just have anal sex? Does he lose his, but she keeps hers on a technicality? The reason you may not have even considered such questions is that most of us subconsciously understand sex as being penis in vagina sex. This is what scholars often refer to as ‘compulsory heterosexuality’ (Tolman, 2006). This doesn’t mean that heterosexuality is literally compulsory, but that our cultural scripts around sexuality are undeniably heterosexual; it has become our ‘normal’. Now, this is undeniably cis-gendered privilege, but it is the product of thousands of years of cultural conditioning. It is only with the tremendous work done by LGBTQ activists over the last fifty years that we have begun to create space to discuss alternatives to boy-girl sex at all. But, there is still a long way to go.  Tampax Advert 1990s Tampax Advert 1990s Even the language surrounding virginity is loaded. The concept of ‘losing’ or ‘keeping’ your virginity suggests that once lost, we are all lacking something and are no longer whole. It also suggests that virginity is something tangible that we had in the first place. You can metaphorically ‘give’ someone your V-Card, but it’s not like they can hang it above their fireplace, or resell it on eBay (although several women have tried and failed to flog their ‘brand new, in box’ on the auction site.) Despite considerable research into hymens, many myths still surround them (Emans et al., 1995). People still believe exercise, and horse-riding can rupture the hymen (they don’t), and Tampax were still reassuring young women that they couldn’t pop their cherries on a tampon as late as the 1990s  Today, the most well-known ‘proof’ of virginity test is blood produced from a ruptured hymen. But, our ancestors didn’t even use the word ‘hymen’ and certainly didn’t go rooting around inside vaginas like they were digging for the cookie dough in a tub of Ben and Jerry's. In fact, medical texts don’t start talking about the hymen until the fifteenth century (Kelly, 2000). None of the Classical physicians make mention of it (Galen and Aristotle, for example). Greek doctor Soranus (yes, really) suggested that any post-coital vaginal bleeding was the result of burst blood vessels, and categorically denied any kind of membrane inside the vagina (Soranus and Temkin, 1994). Many early texts acknowledge that women may bleed when they have sex for the first time, but this wasn’t linked to the hymen. Rather, it was thought that the bleeding was caused by the trauma of penile penetration and was not proof enough of virginity. It was the Italian physician Michael Savonarola who first used the word ‘hymen’ in 1498, describing it as a membrane that ‘is broken at the time of deflowering, so that the blood flows’ (Savonarola, 1498). After this, references to the hymen and its links to virginity became increasingly common. But, just because our ancestors didn’t search for intact hymens does not mean that virginity was not subject to rigorous tests before the hymen became the benchmark for proof of tampering.  Metsy's Elizabeth I, 'The Sieve Portrait' ( c.1583) Metsy's Elizabeth I, 'The Sieve Portrait' ( c.1583) The most famous virgins in the Ancient World were Rome’s Vestal Virgins. The Vestal Virgins were priestesses, dedicated to the Goddess of hearth and family, Vesta. They were chosen at a young age and had to dedicate thirty years of worship and chastity to the city of Rome where they tended the temple flame of Vesta. The punishment for a Vestal having sex whilst on duty was to be entombed alive and left to starve to death. So, how do you test a Vestal’s virginity? Well, some praying is involved. The priestesses were believed to have special connection with the Gods, so when the Vestal Tuccia was accused, she was given the opportunity to conjure a miracle and prove she was still a virgin. According to Valerius Maximus, Tuccia proved her virginity by carrying water in a sieve. She called out, ‘O Vesta, if I have always brought pure hands to your secret services, make it so now that with this sieve I shall be able to draw water from the Tiber and bring it to Your temple’ (Valerius Maximus. and Wardle, 1997). The sieve has since become a symbol of virginity and Queen Elizabeth I was often painted holding one to symbolise no one had taken a bite of her cherry bun. But, if you did not happen to have a sieve to hand there were other virginity tests available to you. (As long as you had a snake, some ants and a cake.) The Roman writer Aelian (175-235 CE) describes a ritual for testing virginity that took place on holy days; "In a grove is a vast deep cavern, the lair of a snake. On fixed holy days maidens bring barley cakes in their hands, their eyes bandaged. Divine inspiration guides them straight to the serpent at a gentle pace without stumbling. If they are virgin, the snake divines the answer and accepts the food, if not, it remains untasted. Ants break up the cakes of the deflowered and carry the pieces outside the grove and thus cleanse the spot. The people get to know of the results and the girls are examined and the one who shamed her virginity is punished" (Harlan, 1995). Quite what this ‘punishment’ was is not elaborated upon, but given that snakes are not widely known for their love of Battenberg, this test seems rather unfair.  To really confirm the seal had not been broken, you needed a bottle of wee. The thirteenth-century text, De secretis muleirum, explains that the urine of virgins is “clear and lucid, somethings white, sometimes sparkling”. The reason that ‘corrupted women’ have ‘muddy urine’ is because of the ‘rupture’ of skin and that ‘male sperm appear on the bottom’ (Lemay and Albertus, 1992). Pissing Perrier is a neat party trick, but there are other signs to look for. William of Saliceto (1210–1277) wrote that virgins “urinate with a subtle hiss,” and if you had a stopwatch handy, they “indeed takes longer than a small boy” (Heimerl and Guilelmus de Saliceto., 2008). Medieval virginity tests are quite urine focused, and fifteenth-century Italian physician, Niccolo Falcucci was also a piss prophet, but he also had a few other tricks up his sleeve. "If a woman is covered with a piece of cloth and fumigated with the best coal, if she is a virgin she does not perceive its odour through her mouth and nose; if she is smells it, she is not a virgin. If she takes it in a drink, she immediately voids urine if she is not a virgin. A corrupt woman will also urinate immediately if a fumigation is prepared with cockle. Upon fumigation with dock flowers, if she is a virgin she immediately becomes pale, and, if not, her humour falls on the fire and other things are said about her" (Kelly, 2000). But, perhaps you are struggling to inspect, listen to or time your intended’s waterworks. In which case, you will need to study her general appearance for the tell-tale clues her flower has been plucked. Before explaining that a virgin’s wee sparkles, Pseudo-Albertus Magnus’ De secretis muleirum explains what to looks out for. ‘The signs of chastity are as follows: shame, modesty, fear, a faultless gait and speech, casting eyes down before men and the acts of men’. (FYI, these are also signs she ordered and ate the Pizza Hut family feast on her own and is praying you don’t find the evidence in the bin.) Magnus continues, "If a girl's breasts point downwards, this is a sign that she has been corrupted, because at the moment of impregnation the menses move upwards to the breasts and the added weight causes them to sag. If a man has sexual intercourse with a woman and experiences no sore on his penis and no difficulty of entry, this is a sign that she was first corrupted. However, a true sign of the woman's virginity is if it is difficult to perform the act and it causes a sore on his member" (Lemay and Albertus, 1992). Of course, once the hymen became the go to virginity test, checking for sparkling, wee that whistled, perky boobs, and the ability to smell coal without wetting one’s self largely fell out of favour. Virginity testing became all about tightness and blood.  Producing bloodied bed-sheets as proof of a bride’s virginity does occur around the world today, although its rare. In certain regions of Georgia, brides have a ‘Yenge’, who is usually an older family member, who will instruct her in what to expect on her wedding night. Traditionally, it was the Yenge’s responsibility to take the bloodied sheets from the marital bed and show them to both families to ‘prove’ the bride was a nookie newbie. Although, the Yenge’s role is largely ceremonial today, in some areas the practice of bloodied sheets still goes on (Georgia Today on the Web, 2017). The bloody sheet test also has a long pedigree. It is found in the bible (Deuteronomy 22:13-21), old medieval romances (Burge, 2016), and it’s said that Katharine of Aragon was able to produce blood stained sheets to prove she married as a virgin when her marriage to Henry VIII was put on trial in 1529 (Kelly and Dershowitz, 2004). Of course, as long as people have subscribed to this deeply flawed test, there have been ways of faking it. Given what was at stake should the gift of a bride’s virginity be unwrapped by someone else before the ‘I dos’, you can understand why a girl would fake it. As long as medical texts have telling us how to prove virginity, they’ve been giving advice on how to restore it. The Trotula is the name given to three twelfth-century Italian texts on women’s health. At least one of the three was authored by a woman, Trota of Salerno, who practised medicine in the southern Italian coastal town of Salerno. The Trotula has this exceptionally devious advice for a girl whose cherry is on the blink. "This remedy will be needed by any girl who has been induced to open her legs and lose her virginity by the follies of passion, secret love, and promises…When it is time for her to marry, to keep the man from knowing, the false virgin will carefully deceive the husband as follows. Let her take ground sugar, the white of an egg, and alum and mix them in rainwater in which pennyroyal and calamint have been boiled down with other similar herbs. Soaking a soft and porous cloth in this solution, let her keep bathing her private parts with it. But the best of all is this deception: the day before her marriage, let her put a leech cautiously on her labia, taking care lest it slip in by mistake; then blood will flow out here, and a little crust will form in that place. Because of the flux of blood and the constricted channel of the vagina, thus in having intercourse the false virgin will deceive the man." (Green, 2002)  The anonymous, thirteenth-century Hebrew Book of Women's Love recommends the following to restore virginity; ‘take myrtle leaves and boil them well with water until only a third part remains; then, take nettles without prickles and boil them in this water until a third remains. She must wash her secret parts with this water in the morning and at bedtime, up to nine days’. However, if you’re in a real hurry you can 'take nutmeg and grind to a powder; put it in that place and her virginity will be restored immediately' (Caballero-Navas, 2004). Nicholas Venette (1633-1698), the French author of the seventeenth-century L’amour Conjugal gave this advice to fake a maidenhead. "Make a bath of decorations of Leaves of mallows, Groundsel, with some handfuls of Line Seed and Fleabane Seed, Orach, Brank Ursin or bearfoot. Let them sit in this Bath an hour, after which, let them be wiped, and examin’d two or three hours after Bathing, observing them narrowly in the mean while. If a Woman is a Maid, all her amorous parts are compress’d and joyn’d close to one another; but if not, they are flaggy, loose, and flouting, instead of being wrinkled and close as they were before when she had a mind to choose us." (Venette, 1984)  by Thomas Rowlandson by Thomas Rowlandson As Hanne Blank argued in her marvellous Virgin: The Untouched History many of the ingredients listed here are astringents or anti-inflammatories that were thought to tighten the vagina. Although Venette doesn’t list it here, one of the most well-known twinkle-tightners was alum water. In Francis Grose’s Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785) he cites ‘pucker water’ as ‘Water impregnated with alum, or other astringents, used by old experienced traders to counterfeit virginity’ (Grose, 1785). Alum, is a class of chemical compound that is used widely today in food preservatives, industry and manufacturing. Insanely, there are numerous websites out there that still recommend alum for tightening the vagina. I will just take this moment to say, please dear God, do not do that to your poor chuff; do your Kegels and keep the faith.  Other than wishing to fake it on their wedding night, another reason a girl would want to pass as a novice is that maidenheads came at a premium. By the eighteenth century, virgins were a lucrative business and any working girl or madam would know how to fake a hymen for maximum profit. Nocturnal Revels (1779) provides explicit details about women selling their virginity several times over, and quotes the famous madam, Charlotte Hayes, as saying a virginity is ‘as easily made as a pudding’ (Revels, 1779). Charlotte goes on to say that she sold her own ‘thousands of times’ (Revels, 1779). The eponymous heroine of the original bonkbuster, Fanny Hill (1749), tells the reader precisely how virginity is faked in the sex industry. "In each of the head bed-posts, just above where the bedsteads are inserted into them, there was a small drawer, so artfully adapted to the mouldings of the timber-work, that it might have escaped even the most curious search: which drawers were easily opened or shut by the touch of a spring, and were fitted each with a shallow glass tumbler, full of a prepared fluid blood, in which lay soaked, for ready use, a sponge, that required no more than gently reaching the hand to it, taking it out and properly squeezing between the thighs, when it yelded a great deal more of the red liquid than would save a girl's honour" (Cleland, 1749). Other sneaky tips include having sex during menstruation to ensure blood, and placing a bird’s heart, or a pig’s bladder stitched up and containing blood, into the vaginal cavity so it will ‘bleed’ on que (Williams, 2006). Despite a deeply ingrained historical belief in the bleeding virgin, this has never been unanimously accepted by the scientific community. There have always been lone voices of reason who recognised this as a load of cobblers. Physicians such as Ambroise Pare not only denied that virginity could be proven with a hymen, he claimed there was such a thing as a hymen back in 1573. Since then there have been occasional whispers that the hymen is not quite the certificate of authenticity it is touted to be. By the nineteenth century, those whispers had become an audible grumble. Dr Blundell questioned the value of this ‘mystic membrane’, and Erasmus Wilson stated that the hymen ‘must not be considered a necessary accompaniment to virginity’ in 1831 (On the Signs of Defloration in Young Females, 1831). Edward Foote wrote that ‘the hymen is a cruel and unreliable test of virginity’ and that ‘physicians know it is a very fallible test of virginity’ in 1863 (Foote, 1863). By the twentieth century, the grumble had become a deafening shout and by the twenty-first century the shouting had been replaced by dramatic eye rolls and exasperated cries of ‘for f**k sake! Not this bollocks again’. The study I referred to at the beginning of this essay identified some 1269 studies in electronic databases that research the validity of virginity testing and overwhelmingly reached the conclusion that you cannot ‘prove’ someone a virgin and hymens tell you naff all about the owner’s sexual past (Olson and García-Moreno, 2017). And yet, the myth persists and women are routinely subjected to pointless and invasive examinations to try and establish their sexual past.  We might have come along way since burying Vestal Virgins alive if they can't carry water in a sieve, but the truth is that virginity testing is still in force throughout the world, and with devastating consequences. We might laugh at the thought of old men inspecting urine for bubbles, but the tests carried out today have no basis in science either. Today virginity examinations are largely carried out on unmarried females, often without consent or in situations where individuals are unable to give consent (Independent Forensic Expert Group, 2015). Virginity testing on schoolgirls has been reported in South Africa and Swaziland to deter pre-marital sexual activity. In India, the test has been part of the sexual assault assessment of female rape victims. In Indonesia, the exam has been part of the application process for women to join the Indonesian police force (Olson and García-Moreno, 2017). But even if you could prove someone’s virginity the issue isn’t really the examination itself (although it’s bad enough), it’s the systems that enable that test and value women primarily on whether or not they are sexually active that are the issue. As long as we continue to demonise and repress female sexuality, the cult of the virgin will continue to thrive. As Voltaire once wrote that "It is an infantile superstition of the human spirit that virginity would be thought a virtue and not the barrier that separates ignorance from knowledge." Notes [1] Despite the social emphasis on keeping your flower unplucked, recent research published by the Journal of Sex Research found that adult virgins of both sexes (aged over 25) face considerable social stigma in the US, and believe that are not desirable as romantic partners. Male adult virgins felt their masculinity was called into question and women believed they were written off as ‘old maids’ (Gesselman, Webster and Garcia, 2016). [2] The Minangkabau of West Sumatra, Indonesia, the Mosuo of Tibet, the Ghanese Akan, the Bribri of Costa Rica, the Garo of Meghalaya, India and the Nagovisi of New Guinea are all regarded as matriarchal societies and all share matrilineal inheritance lines. When property passes from mother to daughter (regardless of paternity), who’s the daddy is of little consequence. The sexual customs of this cultures are far more permissive; unions between men and women are easily dissolved without shame, women are free to have multiple sexual partners, and concepts of adultery, promiscuity, and illegitimacy are not known as they are in the West (Gottner-Abendroth, 1999). Bibliography

Abbott, E. (2000). A history of celibacy. New York: Scribner. Africa Check. (2017). Virginity testing ‘sacred’ but not a science. [online] Available at: https://africacheck.org/reports/virginity-testing-sacred-but-not-a-science/ [Accessed 21 Aug. 2017]. Blank, H. (2008). Virgin. New York: Bloomsbury USA. Burge, A. (2016). “I Will Cut Myself and Smear Blood on the Sheet”: Testing Virginity in Medieval and Modern Orientalist Romance. In: J. Allan, C. Santos and A. Spahr, ed., Virgin Envy: The Cultural Insignificance of the Hymen. London: Zed. Caballero-Navas, C. (2004). The book of women's love and Jewish Medieval medical literature on women. London: Kegan Paul. Cleland, J. (2012). Memoirs Of Fanny Hill A New and Genuine Edition from the Original Text (London, 1749). Hamburg: tredition. Emans, S., Woods, E., Allred, E. and Grace, E. (1995). Hymenal findings in adolescent women: impact of tampon use and consensual sexual activity. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine, 2(3), p.167. Fgmnationalgroup.org. (2017). FGM National Clinical Group - Historical & Cultural. [online] Available at: http://www.fgmnationalgroup.org/historical_and_cultural.htm [Accessed 10 Aug. 2017]. Foote, E. (1863). Medical common sense. New York: The author. Georgia Today on the Web. (2017). Bloody Sheets: An Age-old Tradition Still Held in Georgia’s Regions. [online] Available at: http://georgiatoday.ge/news/2879/Bloody-Sheets%3A-An-Age-old-Tradition-Still-Held-in-Georgia%E2%80%99s-Regions [Accessed 20 Aug. 2017]. Gesselman, A., Webster, G. and Garcia, J. (2016). Has Virginity Lost Its Virtue? Relationship Stigma Associated With Being a Sexually Inexperienced Adult. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(2), pp.202-213. Gottner-Abendroth, H. (1999). The Structure of Matriarchal Societies. ReVision, 21(3). Green, M. (2002). The Trotula. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Grose, F. (2017). Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. Read Books Ltd. Harlan, M. (1995). Roman Republican moneyers and their coins. London: Seaby. Heimerl, C. and Guilelmus de Saliceto. (2008). The Middle English version of William of Saliceto's 'Anatomia'. Heidelberg: Winter. Hobday, A., Haury, L. and Dayton, P. (1997). Function of the human hymen. Medical Hypotheses, 49(2), pp.171-173. Horváth, A. (2011). Of Female Chastity and Male Arms: The Balkan "Man-Woman" in the Age of the World Picture. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 20(2), pp.358-381. Independent Forensic Expert Group (2015). Statement on virginity testing. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 33, pp.121-124. Kelly, H. and Dershowitz, A. (2004). The matrimonial trials of Henry VIII. London: Wipf and Stock. Kelly, K. (2000). Performing virginity and testing chastity in the middle ages. New York: Routledge. Lemay, H. and Albertus. (1992). Women's Secrets: A Translation of Pseudo-Albertus Magnus's De Secretis Mulierum with Commentaries (SUNY Series in Medieval Studies). State University of New York Press. Medievalists.net. (2017). How to Cheat on a Virginity Test. [online] Available at: http://www.medievalists.net/2016/06/how-to-cheat-on-a-virginity-test/ [Accessed 20 Aug. 2017]. Mentalfloss.com. (2017). 6 Modern Societies Where Women Rule. [online] Available at: http://mentalfloss.com/article/31274/6-modern-societies-where-women-literally-rule [Accessed 14 Aug. 2017]. Olson, R. and García-Moreno, C. (2017). Virginity testing: a systematic review. Reproductive Health, 14(1). On the Signs of Defloration in Young Females. (1831). London Medical Gazette: Or, Journal of Practical Medicine, 48, pp.304-306. Savonarola, M. (1498). Practica maior. Venice. Soranus and Temkin, O. (1994). Soranus' gynecology. Baltimore [u.a.]: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press. Stanger-Hall, K. and Hall, D. (2011). Abstinence-Only Education and Teen Pregnancy Rates: Why We Need Comprehensive Sex Education in the U.S. PLoS ONE, 6(10), p.e24658. Tolman, D. (2006). In a different position: Conceptualizing female adolescent sexuality development within compulsory heterosexuality. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2006(112), pp.71-89. Valerius Maximus. and Wardle, D. (1997). Valerius Maximus' "Memorable deeds and sayings". Oxford: Clarendon. Venette, N. (1984). Conjugal love, or, The pleasures of the marriage bed. New York: Garland. Williams, G. (2006). Shakespeare's sexual language. London: Continuum. World Health Organization. (2017). Female genital mutilation. [online] Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/ [Accessed 10 Aug. 2017].

Jonathon Green

8/22/2017 01:46:41 am

‘Women can now pay to have their hymens rebuilt for the marriage market, and the hymenoplasty business is booming.’

Kate

9/8/2017 11:20:39 pm

Fabulous. Thank you! X Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed