|

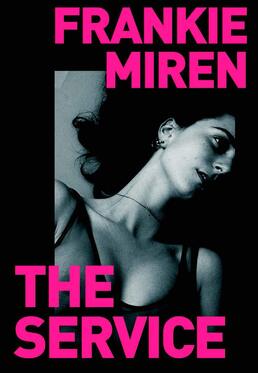

The history of sex work is largely one of missing voices. Given how much has been said, and continues to be said, on the subject, this seems something of a paradox. As does the fact that, historically at least, the people who have been able to say the least about the selling of sex are the sex workers themselves. The voices of lawmakers, pornographers, moralists, and academics have long drowned out those of the people they are talking about, for, or over. Its only within the last 50 years or so, with the emergence of the sex worker rights movement, that those selling sex have been able to carve out their own space in a public debate that continues to marginalise them or reduce them to one voice, one narrative. But there isn’t one, there are legion. It is this multiplicity of perspectives that Frankie Miren captures so beautifully in her debut novel, The Service. Pulling together such disparate viewpoints takes more than a skilled writer, which Miren most certainly is, it takes one who has inhabited them. Miren started working as a sex worker in Amsterdam when she was 18. Over the next ten years she worked all over the world, eventually leaving to tend bar and eventually make it as a journalist. She returned to sex work in her late thirties when a chronic illness made full time work all but impossible. The Service combines journalistic precision with authenticity of lived experience to tell a story of sex work in modern day London. The multiplicity of narratives that crowds around sex work is reflected in the novel’s structure which follows three women, telling three stories about sex work, from three different vantagepoints. Three women, viewed through the prism of sex work, whose understanding is determined, not so much by the subject, but by where they stand in relation to it. Paula is an ambitious journalist who can only see the sale of sex as abusive and campaigns for further criminalisation of prostitution. Lori is a single mum, working illegally in a rented flat in central London, living with the impact of new laws that make it illegal to advertise sexual services online. Freya is student, relatively new to the game, who is learning as much about other sex workers as she is about the job itself. The reader’s own perspective is constantly destabilised not only by the narrative structure but by the careful placement of background characters, all circling one another but never quite aligning. There’s the client who genuinely believes the women he pays to have sex with him do so because they ‘are having a good time too’. There is Jade who ‘literally wish[es] death on all clients’, and Veronica who thinks of sex work as ‘a calling’ and herself as ‘more of a healer’. There are the committed activists campaigning for sex worker rights and those who simply don’t have the time to fight the laws that have made their lives unbearable. There are wealthy sex workers and poor ones. Those whose sole income is sex work and those who dip in and out. Those who are exploited and those who exploit. There are the police who see a young Romanian woman they find in a brothel raid as an obvious victim of trafficking who must be rescued and sent back home, and the woman herself who was simply trying to make rent. There are the radical feminists who see pimping and ‘pop-up brothels’, and the women, whose flat was raided, who were just working together and sharing the bills. (Under British law, a brothel is classified as any residence where more than one person is selling a sexual service.)

The Service deftly weaves fact and fantasy together, creating a fictional world that is all too real. The occupation of a church in Soho, for example, is based on real life events in 1975 when sex workers occupied a church in Saint-Nizier to protest police brutality. The law banning the advertisement of sexual service on third party host sites, such as Craig’s List, is already in force in America. The campaign to criminalise clients (the Nordic Model) has not been successful in England, but has been introduced to several counties, all of which has resulted in an increase of violence against sex workers. The subtle nod to historic and current events gives the novel an urgency and a message that runs more than page deep. Stigma and criminalisation do not keep sex workers safe, and they never have. The Service pushes past stereotypes of sex work as glamorous or degraded and reveals a much more mundane world where women are simply trying to make a living, albeit in exceptional circumstances. Miren does not shy away from the dangers faced by sex workers, but she moves beyond the obvious and shows how social and legal framework that allow such perilous conditions to flourish. The Service is a searing insight into modern day sex work and the arguments that continue to frame and frustrate it. Underneath the fractured narratives and implacable ideologies is one clear message – listen to sex workers. The Service by Frankie Miren is available now (Influx Press) Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed