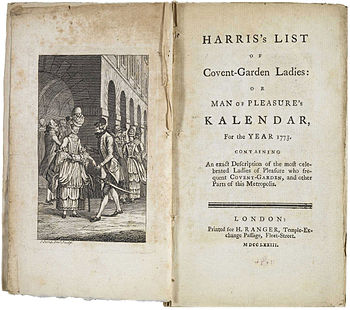

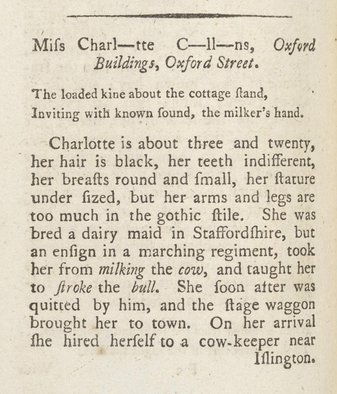

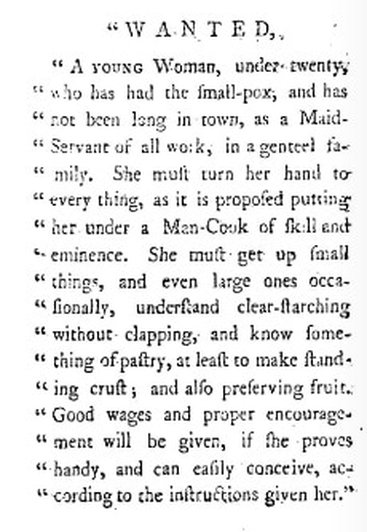

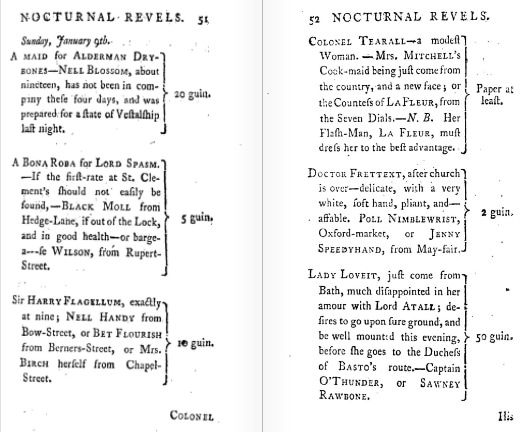

PHOTO: LIAM DANIEL/HULU. PHOTO: LIAM DANIEL/HULU. Moderate spoilers alert "The year is 1763. One woman in five makes a living selling sex.” So opens ITV Encore’s latest period drama; Harlots (Hulu in the US). Created by Alison Newman and Moira Buffini and directed by Coky Giedroyc, the eight-part drama follows the rising fortunes of London bawd, Margaret Wells (Samantha Morton) and her daughters, Charlotte (Jessica Brown Findlay) and Lucy (Eloise Smyth). Harlots has gone beyond simply dusting off the tit crushing corsets and has deftly woven historical facts into the warp and weft of this bloomer dropping, gin swilling, cinematic trupenny upright, and I love it. But, I'm not here to tell you how much fun the show is (and it really is!) I'm here for the history. Harlots tells a hell of a story, but there is more to consider here than a corseted dose of how’s your father in a sepia filter. That Harlots so clearly uses historical truth to embellish the show is what really piques my interest. When fiction embeds itself within historical truth, we are left with a pushmepullyou of facts embellishing stories and vice-versa. Whilst there may seem nothing wrong with exercising creative licence and spinning a good historical yarn, what we must remember is that stories are incredibly powerful things; and whilst fiction is a story that doesn’t need facts, and history is a story that requires facts, stigma is another story made of the two. As Slavoj Žižek argued ‘as soon as we renounce fiction and illusion, we lose reality itself; the moment we subtract fictions from reality, reality itself loses its discursive-logical consistency’ (Žižek, 2004). So when we read a fiction as being historically factual, we need to ask at which end of the pushmepullyou are we? Did this really happen? And when we are dealing with the history of a socially marginalised and vulnerable community (in this case, sex workers), the history we believe becomes even more important as it exerts a palpable influence on current issues and debates. How we write about the history of sex workers matters because whilst the people whose lives are being examined may be long dead, the attitudes, prejudices and narratives that shaped that person’s life are resurrected whenever that story is told. If we read history within the same stigmatised narratives that continue to damage sex workers who are alive today, we are complicit in harm. If you write a history of sex work and use ugly, shaming words like ‘prostitute’, or write from a perspective that assumes all sex workers were women, or were all unhappy, or doomed to a miserable existence, you are using history to reinforce ongoing stigmatised narratives around sex work. Sex work is a highly complex experience and must not be reduced to sensationalised fictions that do nothing to capture the lives of the very people being depicted. So with all of that in mind, what is the ‘real’ history behind Harlots?  "The Dairy Maid's Delight", a drawing by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) "The Dairy Maid's Delight", a drawing by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) Numbers We’ll start with that statistic “The year is 1763. One woman in five makes a living selling sex.” The simple truth is that we do not have accurate estimates for the numbers of sex workers in eighteenth-century Britain (or anywhere else) for several reasons. Sex workers were, and still are, a marginalised, criminalised community and ran the risk of being publicly shamed, punished and even deported if identified; subsequently, few people were open enough about selling sex to collect accurate data. The eighteenth century lexicon did not include words such as ‘sex worker’, but rather used words such as whore, harlot, strumpet or lewd woman. The definition of each of these terms covered women selling sex to those who had sex outside of marriage, or lived with a man they were not married too; so when number of whores are being recorded, it does not necessarily men someone who sold sex for a living. Quantitative data analysis around sex work in the eighteenth century was far closer to what we could politely call ‘guess work’, than anything that would pass peer review today. However, this did not stop people from having a damn good guess.  In 1758, Saunders Welch, a Justice of the Peace for both the County of Middlesex and the City and Liberty of Westminster, published A Proposal to render effectual a Plan, To remove the Nuisance of Common Prostitutes from the Streets of this Metropolis and conservatively estimated there were some 3000 women who made their living selling sex in the capital. When Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz visited London in 1789, he estimated there were 30,000 ladies of pleasure living in the district of Marylebone alone (Archenholz, 1789). Michael Ryan, author of Prostitution in London (1839), estimated that by 1802 there were 80,000 sex workers and some 5000 brothels in London (Ryan, 1839). In 1795, police magistrate Patrick Colquhorn calculated there were 50,000 sex workers in London – which had a population of around 730,000. Viewing Colquhorn's data as the most reliable, modern historian Dan Cruickshank suggests that sexually active women will account for around 250,000 of that figure, which roughly equates to one in five women selling sex in Georgian London (Cruickshank, 2010). As you can see, estimates differ wildly and really the only thing we can say with some certainty is there were more than a few women on the game in eighteenth-century London. But, it shouldn’t come as any kind of surprise that so many women sold sex to earn a crust. Historically, men have always held the money and the power and there was only three ways a woman could access some of that for herself; she could inherit it, she could marry it, or she could shag it. Far from being a last desperate resort, as perilous as it was, sex work could offer a decent income, independence and social advancement in a deeply patriarchal world that barred women from positions of power. Of course, women could try to earn an income as a seamstress or some kind of domestic worker, but this was a long time before Destiny’s Child asked independent women to ‘throw their hands up’; working in the eighteenth century (especially for women) was damn tough. The eighteenth-century wage gap was not so much a gap as a vast, unforgiving ravine with horny sharks at the bottom; and the only kind of employment rights on offer was the right to work yourself to death (preferably quietly and without making a mess.) But, a sex worker could make serious cash, and there were many honeys makin' money. If a lowly female domestic servant could expect a wage of around £2 - 4 a year (with accommodation and food), a sex worker could earn that in one night (Oldbaileyonline.org, 2017). Of course, there was no standard charge for sexual services, and there were kept mistresses who could wouldn't get into bed for less than a hundred guineas (Casonova recorded that Kitty Fisher once ate a thousand guinea note on a slice of bread and butter). But, there were also many destitute people who would exchange sex for food. In 1762, James Boswell walked through London and recorded in his diary that he was "surrounded with numbers of free-hearted ladies of all kinds: from the splendid Madam at fifty guineas a night, down to the civil nymph with white-thread stockings tramps along the Strand and will resign her engaging person to Honour for a pint of wine and a shilling’ (Boswell, 1762). The amount charged by the sex workers featured in Harris’s List varies, but averages at around one guinea per customer, which is slightly over £1 (12 pence to the shilling, 20 shillings to the pound and a guineas was worth 21 shillings.) Despite significant risks to health and well-being, many people sought out sex work and the wealth it promised. Harris's List  The eighteenth-century literary blockbuster, Harris’s List (1757 to 1795) is featured in the opening scenes of Harlots. Harris’s List was an annual almanac of London sex workers. A forerunner to TripAdvisor, the list detailed the appearance, skills, and prices of up to two hundred women selling sex in the capital. One source I heartily recommmend if you want to learn more about the list is Matthew Sangster's research project for "Romantic London". Sangster has created an incredible resource in an online map of Harris's List, using the addresses provided in the 1788 edition here. You can see exactly where these women lived in London, as well as read their description in the list; it's fabulous. The list seems to have been the result of a collaboration between an Irish Grub Street hack and poet, Sam Derrick, and London Pimp, Jack Harris. Only nine known volumes of the list survived today (1761, 1764, 1773, 1774, 1779, 1788, 1789, 1790 and 1793), and they are scattered throughout various archives around the world. There have been a handful of reprints, but until 2005, if you wanted to see the list, an appointment at an archive and a pair of white gloves would have been required. It wasn’t until historian Hallie Rubenhold undertook the herculean task of researching and editing the list in her publication The Covent Garden Ladies: Pimp General Jack and the extraordinary story of "Harris' List" (2005), that the list was dusted off and shown to the public anew. Rubenhold and her work remain the leading authority in the study of the list, and this article is likewise indebted; so, thanks Hallie!  As you may well imagine, Harris’s List was a hugely popular work. As well as being a practical resource, the list also provided titilation. As Delinger notes, the list functions in two ways: ‘names, addresses, and prices all point to their practical use, while the lush descriptions of women also function as soft-core pornography’ (Denlinger, 2002). The list itself straddles the boundaries of fact and fiction; and we will never be able to attest to its accuracy; were Betsy Miles’s breasts ‘of immense size’? Was Nelly Anderson truly a ‘squat, swarthy round faced wench’? Were Miss Simms ‘low countries’ like ‘a well-made boot’? (Rubenhold, 2005). We will never know. Episode one of Harlots opens with an excited group of young women anxiously awaiting their reviews, and with good reason; Harris’s List could make or break the fortune of London’s sex workers. In episode one, Emily Lacey’s favourable review as ‘young votary of Venus’ allows her to leave Covent Garden and approach an elite brothel in Golden Square to seek a better position. Like every profession, sex work was (and still is) densely layered, and a favourable review would allow a girl to command more money, richer clients and go up in the world. A bad review, or an accusation of carrying the pox (like Miss Young of Cumberland Court, who is described as spreading ‘her contaminated carcass on the town’), would see business dry up quicker than sawdust on sick. Despite Jack Harris’s narrative style of a cheeky scamp about town, sampling the delights of the city at random, the selection process was highly competitive; Harris knew the marketing value of his list. The memoirs of Fanny Murray, one of the most celebrated eighteenth-century courtesans, provides valuable insight into the processes. Fanny had to apply to Harris to have her name ‘enrolled upon his parchment list’. She then had to be interviewed, submit to a medical examination, agree give Harris a fifth of the money she earned and sign a contract that stipulated she must forfeit £20 to Harris if she is found to have lied about her health during the examination (Memoirs, 1759). Expensive this certainly may have been, but it could be a worthwhile investment, Harris’s List helped to launch the careers of several London’s top courtesans; Fanny Murray, Lucy Cooper and Charlotte Hayes.  Charlotte Hayes Charlotte Hayes Cast of Characters Harlots has an impressive cast of characters and whilst the plot is fiction, many of the characters are impressions and composites of real lives lived on the fringes of the Georgian underworld. In an interview with The Radio Times, Alison Newman is quoted as saying when they ‘were dreaming up Charlotte Wells (Jessica Brown Findlay), they were thinking about Kitty Fisher’ (Griffiths, 2017). Whilst Kitty Fisher is a fascinating character (you can read more about her here), Charlotte Wells is clearly based on one of the most notorious and successful eighteenth-century courtesans turned madam, Charlotte Hayes. Charlotte Hayes is favourably described in the 1761 edition of Harris’s List. "Were we to enter into an exact description of this celebrated Thais; that is, were we to describe each limb and feature a party, they would not appear so well as taken altogether, in which we must acknowledge her very pleasing; and in our eye (and sure nobody can better tell what is what) she is as desirable as ever". (Harris, 1761) Despite a single entry in the list, a much fuller account of Charlotte’s life is found in another eighteenth-century text, Nocturnal Revels (1779), which you can read at this link. The most comprehensive studies of Charlotte’s life are to be found in Rubenhold’s The Covent Garden Ladies (2005), Dan Cruickshank’s A Secret History of Georgian London (2010) and Fergus Linnane’s Madams: Bawds and Brothel Keepers of London (2011). But, it is Rubenhold's biography of Charlotte that is most clearly expressed in Harlots.  PHOTO: LIAM DANIEL/HULU. PHOTO: LIAM DANIEL/HULU. Charlotte clawed her way up from desperate poverty to become one the most successful bawds in London, and Madam of the King’s Place brothel. When she died in 1813, she had amassed a fortune of over £20,000, achieved celebrity status and hobnobbed with royalty; not bad for a girl from the gutter. Rubenhold’s biography of Charlotte suggests she was the daughter of another London bawd, Elizabeth Ward (who is on record in 1754, accusing Ann Smith of stealing clothing from her.) Rubenhold’s details how Elizabeth Ward bred Charlotte up for a life on the town and eventually auctioned off her daughter’s virginity to the highest bidder, which would have proved ‘one of her mother’s greatest business transactions’ (Rubenhold, 2005). This narrative is certainly played out by Harlots, where Charlotte’s mother, Margaret Wells, is shown taking ‘sealed bids’ for her youngest daughter’s virginity (which she sells twice), just as she did for Charlotte’s some years earlier (Harlots, 2017). Alas, I do not have access to the sources that confirms Elizabeth Ward was Charlotte Hayes’ mother. Nocturnal Revels seems to suggest that Ward was Charlotte’s madam, rather than mother, and ‘initiated her all the mysteries of a Tally-Women’ (Revels, 1779). But, Nocturnal Revels provides explicit details about the selling of virginity several times over, and quotes Charlotte herself as saying a virginity is ‘as easily made as a pudding’ (Revels, 1779). However, rather than her mother selling her virginity, here Charlotte reveals she had sold her own ‘thousands of times’ (Revels, 1779). Whomever Charlotte’s mother was, she managed to secure herself a very rich ‘keeper’ in Robert 'Beau' Tracy. Just like in Harlots, Charlotte financially drained her patron and was ‘notoriously unfaithful to him’ (Revels, 1779). When Tracey died Charlotte ended up in debtor’s prison. It was here that she met and fell in love with an Irish sedan-chairman, Dennis O’Kelly (Daniel Marney in Harlots). According to O’Kelly’s memoirs, before he met Charlotte, he had earned additional income by having sex with wealthy women who hired his chair, also seen in Harlots (O'Kelly, 1788). And it seems that whilst in prison together, Charlotte also called upon Mr O’Kelly’s services. She was soon ‘devoted to him’, and he in turn was ‘devoted not only to her person, but to her purse’ (O’Kelly, 1788). Whilst I do not know how this will play out in the show, the various historical texts tell is that the real life Charlotte’s patronage allowed O’Kelly to quit his job as a bar tender and sedan chair carrier and become a kept man. O’Kelly began calling himself ‘Count’ and after Charlotte had liquidated his debts, he became the owner of the most famous racehorse in Britain, Eclipse. He and Charlotte went on to open the exclusive brothel, King’s Place. A satirical list of services and prices available at Kings are given in Revels, and it gives some idea of just how lucrative this business could be. Mary Cooper, who is found dying of the pox in an alleyway in episode two of Harlots, seems to be based on Lucy Cooper, a courtesan who really did blaze her way through the ranks and beds of the London elite. Lucy’s life is detailed alongside Charlotte’s in Nocturnal Revels, and a description of both Lucy and Charlotte is found in the 1761 edition of Harris’s List; both women achieved fame and fortune, but Lucy did not have the business acumen of Charlotte and failed to save for the inevitable rainy day. In Harlots, Mary Cooper is celebrated for her sexual prowess, street smarts and dazzling beauty. "Mary Cooper, Mary Cooper. ♪ She's had every Lord and Trooper♪ Mary Cooper, Mary Cooper♪ Leaves her lovers in a stupor ♪ Ridin' high, no man can dupe her ♪ London's Venus, Mary Cooper!" The real Lucy Cooper also had a reputation for debauchery and songs were sung about her too. "Must Lucy Cooper bear the bell And give herself all the airs? Must that damnation bitch of hell Be hough’d by Knights and Squires? Has she a better cunt than I Of nut brown hairs more full? That all mankind with do her lye Whilst I have scarce a cull?" (The Gentleman's bottle companion, 1768) Whilst Mary Cooper dies of syphilis in Harlots, Lucy Cooper lived a life of excess and saw her wealthy, elderly protectors die one by one. Finding herself grog blossomed, partied out and the wrong side of thirty-five, Lucy was unable to replace them. Having set nothing aside from her heyday, Lucy could not meet her debts and soon found herself destitute and in debtor’s jail. She died in squalid poverty in 1772, just four years after being immortalised in song as the woman who ‘all mankind’ wanted to lie with. Nancy Birch, the bawd who birches her culls bloody in Harlots also has a real life counterpart in Ms Nancy Burroughs of Drury Lane, who appears in the 1789 edition of Harris’s List. This Nancy was said to use ‘more birch rods in a week than Westminster school in a twelvemonth’ (Harris’s List, 1789). Other women specialising in BDSM that appear in the list include Miss Lee of Soho who is ‘constantly visited of amateurs of birch discipline’, and Mrs Macatney who birches young girls for the amusing of her paying customers, both of whom appear in the 1793 edition. Harriet Lennox (Pippa Bennett-Warner) and Violet Cross (Rosalind Eleazar) are both black sex workers in Harlots and both have real life counterparts. Moira Buffini revelled that Violet was based on a thief who appears in the Old Bailey records, a black woman called Ann Duck who was hung for highway robbery in 1744; “we sort of based Violet on her" (Griffiths, 2017). Harriet bears more than a striking resemblance to the real life story of ‘Black Harriot’. Harriot was brought to Jamaica as a slave, where British born plantation owner, William Lewis, fell in love with her and they married. Upon moving back to England, Harriot learnt all the airs and graces of high society, but when Lewis suddenly died, she found herself in a desperate situation. However, Harriot decided to take this lying down – quite literally; she turned to sex work and eventually opened her own establishment, becoming the only black madam in London (Arnold, 2010). Trade in Virgins Sex work is a highly complex experience that resists simple stereotypes; sex work in the eighteenth century was no different. There was a dark side and for all the celebrated grande horizontals, when there is that much money at stake, many people were chewed up and spat out by the cities’ never ending demand for flesh. Harlots depicts the eighteenth-century sexual obsession with virgins; as Lady Repton quips in episode one at the auctioning of Lucy Wells’s virginity, ‘my husband loves a hymen’. In Nocturnal Revels, Charlotte Hayes discusses how easy it is to fake a virginity, we also see this trick in Fanny Hill where Fanny is instructed in how to fake a maidenhead; "In each of the head bed-posts, just above where the bedsteads are inserted into them, there was a small drawer, so artfully adapted to the mouldings of the timber-work, that it might have escaped even the most curious search: which drawers were easily opened or shut by the touch of a spring, and were fitted each with a shallow glass tumbler, full of a prepared fluid blood, in which lay soaked, for ready use, a sponge, that required no more than gently reaching the hand to it, taking it out and properly squeezing between the thighs, when it yelded a great deal more of the red liquid than would save a girl's honour". (Cleland, 1749) This tells us two things; firstly, women have been faking things in the bedroom for a long time; secondly, there was such a demand for virgins, knowing how to pass yourself off as an innocent was a staple of any self-respecting harlot’s repertoire. But, for every virginity faked, there were real girls offered up for sale  'Nocturnal Revels' (1779) 'Nocturnal Revels' (1779) William Hogarth’s 1732 A Harlot's Progress (a series of engravings) depicts a young Moll Hackabout who arrives in London fresh from the country, only to be tricked into prostitution by the cunning bawd, Elizabeth Needham. (In 1731 Mother Needham was convicted of keeping a disorderly house and sentenced to be pilloried, she did not survive the experience.) The madam seeking out young girls and tricking them is also seen in Harlots when Lydia Quigley stalks registry offices and stage coaches to find virgins to offer up to well-paying clients. Nocturnal Revels details how Charlotte Hayes procured an endless supply of new ‘nuns’ for her ‘cloister’. Just as Lydia Quigley did in Harlots, Charlotte would dress in a ‘plain and simple manner’ and approach employment offices, searching for any young girl who was seeking domestic work. Charlotte would then tell her she required a maid for her mistress and offer ‘very handsome’ wages. The unsuspecting victim would be taken to a house, plied with drink and be put to bed, only to wake in the night being raped by whomever had paid Charlotte for a virgin. Revels tells us after such a traumatic experience, the victim would be given a few guineas and removed to the ‘nunnery’ in King’s Place ‘in order to make room for a new victim, who is to be sacrificed in the like manner’ (Revels, 1779). When victims could not be procured in this way, Charlotte and other bawds placed advertisements, like the one opposite, in newspapers to bring the girls to them.  Portrait of Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer by William Hogarth from the late 1750s, parodying Renaissance images of Francis of Assisi. Portrait of Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer by William Hogarth from the late 1750s, parodying Renaissance images of Francis of Assisi. Hellfire Clubs In Harlots, Lydia Quigley is supplying virgins to an anonymous, but aristocratic and powerful group of men; it is later revealed these men are murdering these girls. The eighteenth century saw the rise of the Hellfire Clubs across Britain and Ireland. These were exclusive, secretive clubs for wealthy libertines who met to engage in ‘the most impious and blasphemous Manner, insult the most sacred Principles of Holy Religion, affront Almighty God himself, and corrupt the Minds and Morals of one another’ (Gordon, 1721). The clubs were shrouded in mystery and historians have long tried to understand exactly what happened there. Rumours about Satanic abuse of women, devil worship and debauched behaviour circulated around the clubs from the beginning. Did these rich men really deflower virgins and worship the devil, or was it simply as case of, as Evelyn Lord suggests, ‘wealthy men with too much time and licence on their hands, wanting to assert their masculinity’ (Lord, 2010). The most notorious club was formed in 1746 by Sir Francis Dashwood with the motto "Fais ce que tu voudrais" (Do as you will). Lord Sandwich, Lord Bute, the Duke of Queensbury, the Prince of Wales and even Benjamin Franklin were all rumoured to be members (Arnold, 2010). Whist we will probably never know exactly what happened there, the public have always been willing to believe the very worst of them; including the kidnap and rape of virgins. It seems the secretive world of the Hellfire Clubs provided inspiration for the elite group of aristocrats seeking out and murdering virgins in Harlots. Harlots is a delicious peep up the skirt of the eighteenth-century sex trade. Far from being a make believe world, here fact and fiction lie side by side in a sweaty bed, smoking a post-coital cigarette and asking ‘how was it for you?’ The lives held up here are nods to history, but we must remember that the lives of the infamous, people like Charlotte Hayes, Black Harriot and Lucy Cooper, have always been subject to sensationalism. What we know about them is left to us through a series of texts that were designed to inflame the senses and have us clutching our pearls whilst eagerly turning the page for more. For me, the most fun part of Harlots are the background details; the reusable condoms, the women squatting over basins to wash themselves between clients, the perils of pregnancy, butter as lubrication, and the Foundling Hospital - all documented facts about sex in the eighteenth century. (If you would like to read more about birth control and abortion in the eighteenth century, you can read another article I wrote here.) I would urge you to enjoy Harlots for the fantastic romp in the hay it is, and view its reference to historical facts as the delicious sprinkles on top. But, remember a little history can be a dangerous thing and must not be understood to be the full picture. If you want to learn more about sex work in the eighteenth century, I cannot recommend Dan Cruickshank’s Secret History, or Rubenhold’s Covent Garden Ladies enough. And once you have read that, please read about current sex workers and sex worker rights. Historical sex work can be bawdy fun because it allows us to look at a distance and to tell fun stories, but always remember this is the history and heritage of sex work today, and that such stories really do matter to the people fighting the same systems today. Works cited Arnold, C. (2010). London and its vices. 1st ed. London: Simon & Schuster Ltd.

Boswell, J. and Wain, J. (1991). The journals of James Boswell, 1762-1795. 1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. Cleland, J. (2012). Memoirs Of Fanny Hill A New and Genuine Edition from the Original Text (London, 1749). 1st ed. Hamburg: tredition. Cruickshank, D. (2010). The secret history of Georgian London. 1st ed. London: Windmill. Cruickshank, D. (2010). The secret history of Georgian London. 1st ed. London: Windmill. Denlinger, E. (2002). The Garment and the Man: Masculine Desire in Harris's List of Covent-Garden Ladies, 1764-1793. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 11(3), pp.357-394. En.wikisource.org. (2017). Cato's Letter No. 29 - Wikisource, the free online library. [online] Available at: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Cato%27s_Letter_No._29 [Accessed 24 May 2017]. EVELYN LORD. (2010). The Hellfire Clubs. 1st ed. Yale University Press. Griffiths, E. (2017). Meet the real-life women who inspired ITV's Harlots. [online] RadioTimes. Available at: http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2017-03-27/meet-the-real-life-women-who-inspired-itvs-harlots [Accessed 23 May 2017]. Harris, J. and Rubenhold, H. (2007). The harlot's handbook. 1st ed. Stroud: Tempus. Kelly, J. (2010). Clubs and societies in eighteenth-century Ireland. 1st ed. Dublin: Four Courts. Linnane, F. (2011). Madams. 1st ed. Stroud: The History Press. Lord, E. (2008). The hell-fire clubs. 1st ed. New Haven: Yale University Press. Memoirs of the celebrated Miss Fanny M-. Vol. II. (1759). 1st ed. London: Printed for M. Thrush, at the King's-Arms, in Salisbury-Court, Fleet-Street. Memoirs of the celebrated Miss Fanny Murray. Interspersed with the intrigues and amours of several eminent personages. Founded on real facts. (1759). 1st ed. Dublin: Printed by S. Smith. O'Kelly, D. (1788). The genuine memoirs of Dennis O'Kelly, Esq. commolny [sic] called Count O'Kelly: ... 1st ed. London: Printed for C. Stalker. Oldbaileyonline.org. (2017). London History - Currency, Coinage and the Cost of Living - Central Criminal Court. [online] Available at: https://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Coinage.jsp#reading-costofliving [Accessed 21 May 2017]. REVELS. (1779). Nocturnal Revels: or, the History of King's Place and other modern nunneries ... By a Monk of the Order of St. Francis [i.e. of the burlesque Order of St. Francis, of Medmenham Priory] ... Second edition, corrected and improved, with ... additions. 1st ed. London: M. Goadby. Romanticlondon.org. (2017). Mapping Harris’s List of Covent-Garden Ladies (1788) – Romantic London. [online] Available at: http://www.romanticlondon.org/harris-list-1788/#14/51.5119/-0.1067 [Accessed 24 May 2017]. Rubenhold, H. (2012). Harris's list of Covent Garden ladies. 1st ed. London: Doubleday. Russell, K. (1983). Recent Book: Harris's List of Covent Garden LadiesAnonymous: Harris's List of Covent Garden Ladies. Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing. £4.95. The Police Journal, 56(2), pp.206-207. Ryan, D. (2013). Blasphemers & blackguards. 1st ed. Dublin: Merrion. Ryan, M. (1839). Prostitution in London, with a comparative view of that of Paris and New York. 1st ed. London: H. Bailliere, 219, Regent Street. Paris. The Gentleman's bottle companion. (1979). 1st ed. Edinburgh: Harris. Žižek, S. (2004). Tarrying with the negative. 1st ed. Durham: Duke Unversity Press.

Victoria Lane

5/25/2017 07:38:53 am

eek I didn't realize there would be spoilers in this article. I'm only on Episode 3. Can you put a warning in the article for those that may not know that there are spoilers ?

Emily Ann

5/26/2017 10:50:45 am

Thanks so much for a thoughtful, well-written article. I found you through twitter and am excited to read more from you! Thanks again - you're great!

Richard Davies

7/31/2017 08:05:51 am

We enjoyed your excellent article which we came across. Whilst researching our 18th century pastel of Lucy Cooper after Frans van der Mijn.If you give us your email address we will gladly send you a copy.Richard and Dorli Davies Bournemouth Comments are closed.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed