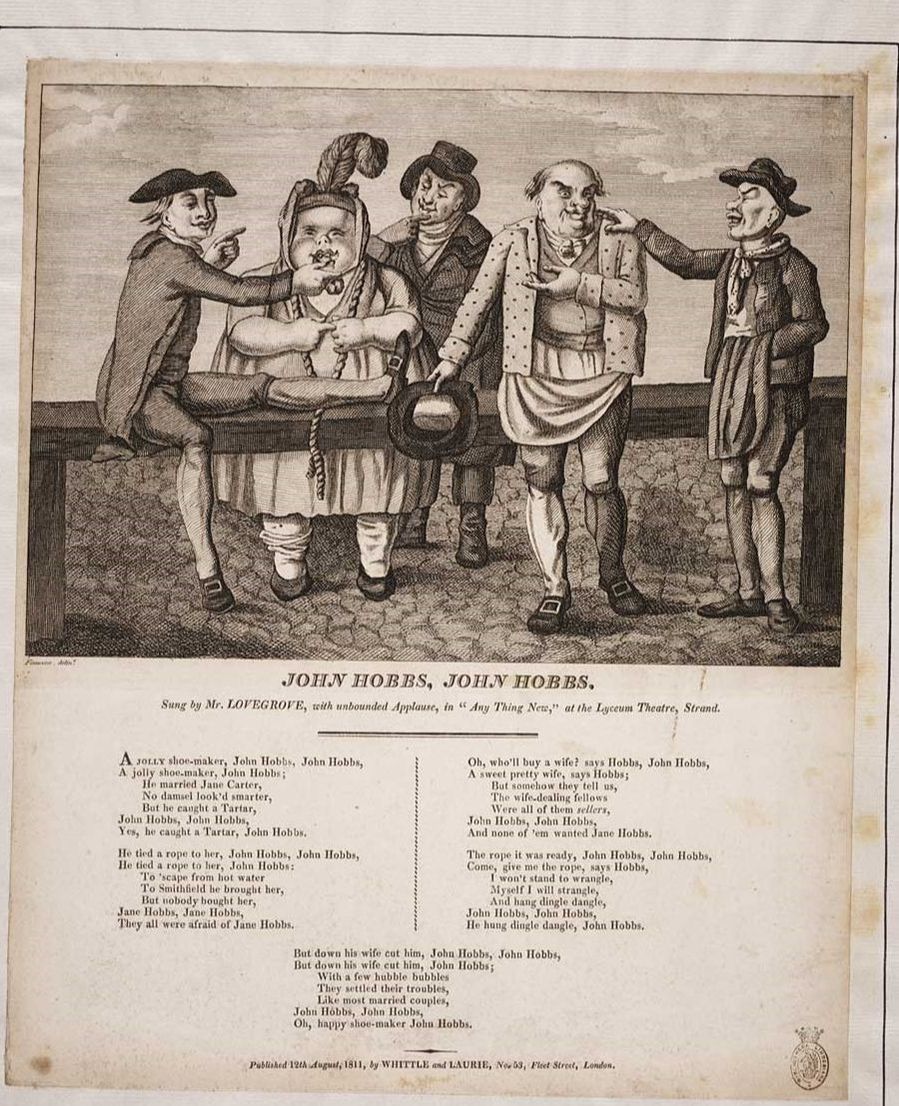

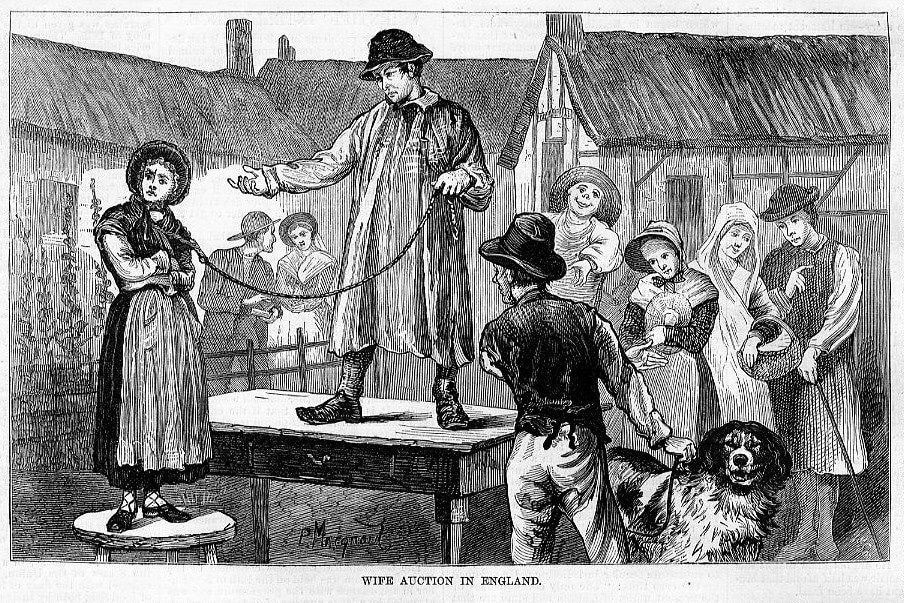

‘British Institution’ or ‘British Scandal’: Spouse-Selling in Victorian Britain by Lauren Padgett12/2/2017 Lauren started her doctoral studies with the Leeds Centre for Victorian Studies at Leeds Trinity University in September 2014. Her research explores representations of Victorian women in museum displays in the Yorkshire and Humber region. Her wider research interests include hidden histories in museum displays and collections, and Bradford's local history. Lauren has a particular interest in Victorian wife-selling in the Yorkshire region, which she has presented and published on. She is also interested in how object handling and museums (via fieldwork and site visits) can enhance and aid Higher Education pedagogy. You can follow her at @LaurenPadgett24 ..................................... After months of promise and disappointment (sorry Kate), I have finally written a blog for Whores of Yore. I had put my spouse-selling research to one side for a while to focus on my doctoral studies. Revisiting this research has been an absolute pleasure so I would like to thank Kate for this opportunity. This blog will hopefully introduce you to the fascinating, curious and intriguing ‘British institution’ or ‘British Scandal’ of spouse-selling in Victorian Britain.(1) .......................................... A wife has a halter around her neck, and her husband is holding the end of it as they walk towards the marketplace. Once there, she stands on a raised block and a bustling crowd surrounds her, drawn by the sound of a bellman signalling their arrival. An auctioneer announces the sale of this wife and starts taking bids from men in the crowd. After several bids, some made in jest, a genuine highest bidder is found. ‘Going once, going twice, sold!’. The buyer shakes the husband’s hand, gives him the agreed amount and takes the end of the halter from him. The buyer (or new husband) walks away with his newly purchased wife to the crowd’s cheers, while the seller (ex-husband) walks away with his money lining his pocket. Which country do you think this scene took place in? Which period or century did this take place in? Would you be surprised to know that this scene occurred in Victorian Britain? My doctoral research is not about spouse-selling or wife-selling (I wish it were though). It became a side research project, or distraction, of mine and had many strands to it. My research focusses on British spouse-selling, particularly in the Victorian period and Yorkshire region. I refer to it as spouse-selling as I research the sales of wives and husbands (a rarity but there are cases of husband-sales, as detailed later). I am also interested in visual representations of wife-selling in paintings, sketches and woodcuts (some of which you will see), and literary depictions of wife-selling in ballads, poems and novels – the most famous being in Thomas Hardy’s The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886). It is a topic that fascinates other people as well as myself; it seems to capture the imagination. The wife-selling ballad ‘John Hobbs’, about a husband called John who tries to sell his wife, certainly caught mine when I first came across it. It is my favourite wife-selling ballad for two reasons, as illustrated in the verses below. Firstly, no man wants to buy Jane, the wife (*cue pantomime ‘Awww’*) and secondly, it has a bawdy ending for the married couple (*wolf whistle*): Oh, who’ll buy a wife? Says Hobbs, John Hobbs; A sweet pretty wife, says Hobbs. But, somehow, they tell us The wife-dealing fellows Were all of them sellers, John Hobbs, John Hobbs. And none of them wanted Jane Hobbs. … They settled their troubles, Like most married couples, John Hobbs, John Hobbs, Oh, happy shoemaker, John Hobbs.(2) Other researchers have examined British wife-sales in great detail, qualitatively and quantitatively.(3) Samuel Pyeatt Menefee literally wrote the book on British wife-selling, while E. P. Thompson contributed a very informative chapter on it, as have John Gillis and Lawrence Stone. These researchers looked into various facets of British wife-selling, from the type of sale, the prices wives were sold for to the geographical locations of sales. Using this historiography and some of my findings, I will outline the custom of wife-selling and share some cases of much rarer husband-selling.(4)  Figure 1 This image accompanied a print of the ballad 'John Hobbs'. At a conference when reading a paper about wife-selling, I showed this image and asked the audience if, like me, they thought that the gentleman on the left was inserting something phallic into the wife’s mouth – WoY’s Kate was one of the few brave enough to agree with me. ‘Rare Oddities’?: The Custom of Wife-Selling The origins of wife-selling in Britain are debated with Stone dating the practice back to the sixteenth and seventeenth century; the first recorded case occurred in 1553.(5) Menefee, however, has argued that this ‘established British institution’ is Anglo-Saxon, practised as early as the eleventh and twelfth century.(6) The custom of wife-selling was seen by many who practised it as a legitimate method of ‘public self-divorce’ and marriage.(7) The act of wife-selling not only ended the marriage between the seller-husband and sold-wife but also signified the new marriage between the buyer-husband and purchased-wife. Wife-sales are largely associated with the ‘plebian’ class, particularly those in rural communities and small towns, according to Gillis.(8) There is, however, a unique case of upper-class involvement. Henry Brydges, the 2nd Duke of Chandos, allegedly came across a wife-sale in Newbury, London, and ‘smitten with her beauty’ bought the wife for half a crown to ‘free her from a harsh and ill-conditioned husband’. She initially became his mistress as he too was married, but when his wife and her old husband had died, they married on Christmas Day in 1744.(9) Until the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act, which authorised newly formed civil Divorce Courts to deal with divorce cases, there were legal and illegal ways of ending marriages, such as separation mense et thoro; annulments; private separation; an expensive private Bill; desertion; or wife-selling.(10) Desertion and wife-selling were attractive options for the lower classes as these methods did not require the involvement of Parliament, courts or the Church and were not expensive like the others. My focus on wife-selling in the Victorian period is because, despite the 1857 Act, which was supposed to make divorce more accessible for the lower classes, many wife-sales still occurred after the 1857 Act. Menefee found 108 wife-sale cases between 1837 and 1901, the Victorian period. Some even took place in the twentieth century; one of the last recorded wife-sales occurred in 1913 in Leeds.(11) Now the background information to wife-selling has been covered, the following sections provides some broad generalisations about wife-sales, but it is important to keep in mind that every sale was different and some truly unique. This whistle-stop tour will explain the different types of sales, their formats and characteristics, the prices that some wives were sold for and identify which region practised the custom more than others. Wife-sales can be broadly categorised as one of three types: sale by public auction; sale by public sale; or sale by private agreement. Sales by public auction took place in communal or public spaces, like marketplaces or outside public houses, sometimes with an auctioneer to take bids and usually with a pre-determined buyer (such as the wife’s lover). Sales by public sale were sale transactions and agreements between the seller-husband, buyer-husband and wife in a public space for others to witness. Sales by private agreement between the seller-husband, buyer-husband and wife were conducted with privacy (usually the back rooms of public houses) with selected witnesses present and/or written agreements, which were sometimes prepared by lawyers. The vast majority of wife-sales occurred with the consent of the wife. Thompson found only four cases of wife-sales between 1760 and 1880 that had occurred with the ‘wife not consenting’. Of these four cases, ‘three of the four cases . . . did not result in sales’ subsequently.(12) It is worth noting that a few wives were not bought by men intending to be their new husbands but in fact their family members. Thompson defined these cases as ‘arranged divorce’ as wives were bought by members of her family (such as her brother, brother-in-law or mother) to free her from an unhappy marriage. Thompson found ten examples of these kinds of wife-sales occurring between 1760 and 1880.(13) The format of public auctions and public sales were as follows. The husband would bring his wife, who often had a halter around her to resemble livestock, to a communal place. If it was a public sale, the buyer-husband might have accompanied the seller-husband and wife there or met them there. A bellman may have announced the start of the auction or sale, and an auctioneer would usually oversee auctions. In a pantomime fashion, there was audience participation with men making false bids in auctions with the understanding that a price and buyer was probably pre-arranged. Although, there were some wife-sales by public auction that occurred without a pre-arranged buyer in mind, so the auction was open to any bidders. These sales had probably been advertised in the days before it to drum up interest and potential bidders. Public auctions and sales were ritualistic and symbolic. The halter was seen as a critical element to the custom. In fact, one wife-sale in Bradford in 1858 was deemed void as ‘it was afterwards discovered that some formality, considered essential, had been overlooked’ – the halter and, interestingly, a whip. A re-sale was arranged a few days later and this time ‘the accessories [were] not overlooked’ as Martha, the wife, was led there by a ‘halter decorated with red, white and blue streamers’ and a ‘whip being duly prepared’.(14) The public arena or communal location created witnesses to the transaction, whether it was by public auction or public sale, to let the community know that one marriage had ended and another begun. The act of wife-selling, particularly with written agreements and witnesses, was thought to offer some legal protection, or, at the very least, provide evidence or witnesses that could be used if any future legal proceedings were brought against those involved. It protected the buyer-husband from later being sued for criminal conversations (a legal euphemism for having an affair) with the wife by the seller-husband. It was a public declaration or witnessed agreement that the seller-husband was no longer financially responsible for the sold-wife, including any debt she accrued. In theory, it prevented the sold-wife from claiming her ex-husband’s estate upon his death and also prevented the seller-husband from claiming any entitlement to the sold-wife’s property and goods. The price of wives varied from little amounts to quite high sums. Goods, as well as money, were exchanged. Anna Clark stated that "The small amounts for which women were sold could be seen simply as token payments, yet they may have served as a contemptuous expression of how little some husbands valued their wives."(15) I, however, am inclined to think that small amounts of money and goods were exchanged in a tokenistic way to seal the deal and legitimise it. Similar to business deals today where something might be sold for a penny or £1 just to legitimise the transaction. In some cases where the wife had an affair and was subsequently sold to her lover, the price may have reflected agreed compensation to the cuckolded seller-husband. Wife-sales did not occur as means to generate income or raise funds for the seller-husband. As buyer-husbands belonged to the lower classes, except the Duke of Chandos, high amounts could not have been paid anyway. Here are some examples of monetary amounts and goods exchanged in wife-sales;

Except for Carlisle, the other places listed are in Yorkshire which is the region I am particularly interested in. I am slightly bias towards Yorkshire with it being my county, but both Thompson and Menefee noted a high occurrence of wife-sales in Yorkshire compared to other regions, particularly in the mid-to-late nineteenth century when the custom was becoming less frequent and dying out in other parts of the country. Menefee said that ‘by the late 1880s the institution seems to be confined largely, although not exclusively, to the industrialized north of English’ due ‘to the tenacity with which Yorkshiremen are said to cling to old ways’.(17) Of the 108 Victorian wife-sale cases Menefee identified, 27 (25%) were in Yorkshire.(18) I found two other Yorkshire cases not identified by Menefee. ‘. . . that’s more than you would fetch’: Husband-Sales When I started my research, it was purely just about wife-selling as I had not given much thought to the possibility of husband-sales and, to be fair, Menefee and Thompson had not either.(18) What prompted me to look into husband-sales was the alleged parting words of a sold wife. In 1849, a man called Ashton had been in Hull General Infirmary receiving medical treatment. While in hospital, his wife, described as a ‘buxom young woman’, eloped with a ‘paramour’ ‘taking with her a great part of the husband’s effects’. When cuckolded Ashton arrived home and discovered what had happened, he tracked the two lovers down, and, after negotiations, all parties agreed to a wife-sale. A public sale occurred in Goole marketplace (in East Yorkshire) with ‘a little spirited competition’ before she was sold to her lover for 5 shillings and 9 pence (5s.9d). Before leaving with her new husband, the wife snapped her fingers at her ex-husband and said ‘There, good-for-nought, that’s more than you would fetch’.(19) This sassy response made me stop and think. Was she joking, a cruel jibe to insult her ex-husband, or could he have been the sold party rather than her? Did wives sell their husbands in nineteenth-century Britain? Although a rarity, I found a few cases. In 1839, at the Tyrone Assizes in Ireland, details of a husband-sale came to light. Henry Mullen (alias O’Neile) was charged with bigamy having married his second wife when his first was still alive. Mullen tried to prove that a disturbance during the marriage ceremony with the second wife had made it ‘incomplete’ therefore, he argued, he had not committed bigamy (although he had intended to). Mr Mullen cross-examined his alleged second wife, Jane Moffatt, and she admitted that she had purchased him from his first wife for £3 ‘thinking [him] very cheap at that’. Another witness supported this, claiming that the second wife ‘had exercised dominion in all things, looking upon [Mullen] as her obedient slave’. The jury found Mullen guilty of bigamy, and he was sentenced to seven years transportation.(20) The witness’s testimony that he was the buyer-wife’s ‘obedient slave’ is interesting. It suggests submission at best, and servitude or enslavement at worse, which in unusual in the reporting of British spouse-sales and even more unusual in terms of the power dynamics of their marriage with the wife having such open and apparent authority over the submissive husband. In Birmingham in 1853, William Charles Capas was charged ‘with having assaulted [his] wife’. The Court heard that the previous year, Capas and been ‘leased to another female’. A contract had been drawn up by a lawyer for £1 and 15 shillings (£1.15s) which Cappas and Emily Hickson, a spinster, signed to agree to ‘live and reside together, and to mutually assist in supporting and maintaining each other during the remainder of their lives’. Capas was fined 2 shillings and 6 pence (2s.6d) for the assault.(21) Around 1888, a married man fell in love with a young woman while on route to Australia. The woman wrote to his wife in England asking to purchase him. The wife initially asked for £100, but £20 was eventually agreed. Legal documents were prepared and signed, and the husband then married his new love in Australia.(22) As demonstrated here, with the Irish husband-sale and the Newbury wife-sale with the Duke of Chandos, it was not uncommon for wife- and husband-sales to be followed by actual marriage ceremonies but risk of being accused of bigamy like Mullen was. The same year, courts at Wolverhampton heard about a husband who had been sold to another woman for £5. When the money had run out, the seller-wife demanded him back.(23) In 1893, a divorce case went through the courts, and it was revealed that the wife had attempted to sell her husband for just three halfpence.(24) What these cases demonstrate is that husbands were sold for much more substantial sums of money than wives and that husband-selling was a much more hidden and private custom compared to wife-selling. These men were spared the halter and the marketplace as all these sales were private agreements made away from prying eyes and baying crowds. Husband-sales flew under the radar, going unnoticed except by the local community in which they lived. It is not until the husbands found themselves in court answering to charges of bigamy or domestic violence that the sale came to light and newspapers reported the husband-sale retrospectively. The husbands that were privately and quietly sold and lived happily ever after with their buyer-wives are lost in history. I believe that husband-selling was probably more common than what can be accounted for due to a lack of surviving historical evidence and its more private practice. A ‘British Institution’ or ‘British Scandal’? When I first started researching British Victorian wife-selling, I could not understand why a woman would allow herself to be scandalised by being publicly sold like cattle or for belittling amounts of money or goods. Why would a wife allow their husband to swap them for a dog or exchange them for a pint of beer? How could they accept it? Why would they go through with it? However, after a few years of research, I can conclude that there is a sense of agency with these wives, privately sold in the back room of a public house or stood on a raised platform in a busy marketplace. Now I can understand why wives consented to be sold, whether the reason was to be freed from an unhappy marriage and this was the most attainable and achievable way of doing it or to be able to start a new life with their lover. Even the women that were sold by auction to the highest bidder on the day (as opposed to a pre-arranged buyer or lover) were reported to be ‘“in high glee”. . . “very happy”, “much pleased”, or “eager”’ with their new husbands.(25) Of the four wife-sales identified by Thompson as occurring without the wives’ consent, three of those wives objected to the sale that took place without their knowledge and did not uphold it. Thinking of the Irish husband-sale case and the suggestion of him being more of a servant or slave than a husband, so far I have not come across any British Victorian wife-sale cases with a bought-wife been treated as anything other than a wife. It is highly probable that more than four wives were sold without consent or that bought-wives were mistreated by buyer-husbands, but there is a lack of surviving evidence to support this, or it has not been discovered yet. The ritualistic elements of wife-sales with the halter and the pseudo-legal elements of witnesses, written agreements and token payments suggests that there was a level of respect of the custom or institution of wife-selling and it appears that it was very rarely abused. I can say that the vast majority of the British wives sold in the Victorian period were willing participants in this custom, using it as a means to improve, better or reclaim their lives. Future Research Most of the research around wife-selling, and indeed even the research in this blog, provides only a snapshot of that moment – the act of the sale, and sometimes the moments leading up to and immediately after it. This is because previous research primarily used newspaper articles that reported wife-sales. Like Menefee and Thompson, I too started with newspaper reports. Most newspaper reports of wife-sales begin with the involved parties making their way to the sale and then the buyer-husband and sold-wife heading towards the sunset together afterwards – or the ‘railway to Sheffield’ in the case of a Rotherham wife-sale in 1839.(26) Therefore research into wife-selling has been limited to the whim of the reporting journalist, what information they chose to report on and how to report on it. Some reports are brief and factual while some are dramatised with lots of vivid descriptions and allegedly speeches and conversations. When I initially started reading existing research and contemporaneous newspaper reports about wife-sales, while fascinated with the details of the sales, I frustratingly wanted to find out more about the people involved and go beyond the sale. To me, the individuals involved with spouse-selling, whether they are the seller, the buyer, the sold party or a spectator/witness, should not be defined by that single moment and research should not be limited to it. I certainly did not want to view or present these women as ‘sold-wives’ only as they were much more than that and their sale and purchase, while unusual, was a small (albeit significant) part of their lives. I wanted to see the bigger picture, rather than view their lives through this one pixel. I wanted to explore the wider social history around the spouse-sales, particularly the aftermath of sales. William Marshall may have sold Mary to John Webster at Thirsk Cross in 1855 for 2 shillings 6 pence (2s.6d), but how long had William and Mary been (unhappily) married? How long did John and Mary’s marriage last after the sale? Where did the newly-weds live afterwards? Did William re-marry? How did the children of William and Mary fare? Did the children stay with their father, William, or go with the mother, Mary, and her new husband John? This is where my research differs from what has come before. I have been using other sources to piece together and uncover this wider history.(27) This is allowing me to understand the circumstances leading up to and the aftermath of some sales as well as the individuals involved. Tracing the aftermath of the Thirsk wife-sale, for example, I found a usual household set-up of a ménage et trois with William (the seller-husband), John (the buyer-husband) and Mary all living together in one house with several children of questionable paternity.(28) This fascinates me more than the sale itself. I hope that after my PhD is completed, either through a Post-Doc research project, for a book or just to satisfy my own curiosity, I can explore this fascinating yet under-researched aspect of spouse-selling further.

4 Comments

Tim

12/2/2017 01:40:06 pm

This is a fantastic and fascinating post! I had no idea this practice even occurred, and up to such a late date.

Reply

Eric Edwards

12/3/2017 08:49:23 am

This was humorously depicted in the movie "Paint Your Wagon". I didn't realize that "auctioning a wife" had historical roots.

Reply

Boitshoko Buthelezi

12/23/2017 06:06:54 am

Great read indeed

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed