|

Emma Rees is professor of literature and gender studies at the University of Chester, where she’s also director of the Institute of Gender Studies. Her book, The Vagina: A Literary and Cultural History came out in paperback in 2015.

Just over a year ago I was invited on a short book tour of Florida. It was only my second time in the States and it was a culture shock in many ways (not least in terms of the near-ubiquitous media coverage of an utterly improbable presidential candidate called Donald Trump). The tour took me from the west coast, via Alligator Alley to the east coast and Miami. It was here that, in a supermarket, I saw a strong household cleaner on the shelves, its reverse-side packaging crammed full of safety warnings about its toxicity, and its front-side showing the brand’s name – Lysol – in a cursive script that was eerily familiar. For part of my talk – ‘Vulvanomics’ – that I was touring then, and still regularly present, looks at the lineage of misogyny that runs through the attempts of major global companies to monetise a pervasive cultural fear of women’s genitals.

Growing up in the ‘developed’ world, women are exposed from a very young age to the idea that their vaginas (and their vulva, clitoris, and labia, too) are hateful, unruly, unloved, uncharted, unincorporated, even unnamed. For what does it mean for women when the only word that describes the whole kit ‘n’ caboodle is also the most offensive word in the English language? That noxious bottle of Lysol with its familiar font caught my eye because of its shameful history – a history predicated on the idea that vaginas are dirty. The disinfectant I saw was manufactured by Reckitt Benckiser, a company founded in the early 1800s in the United Kingdom, with operations today in more than 60 countries, specializing in manufacturing cleaning products. Reckitt Benckiser’s net revenue for 2015 was £8,874 million, with ‘Health and Hygiene’ making up 74% of this profit.

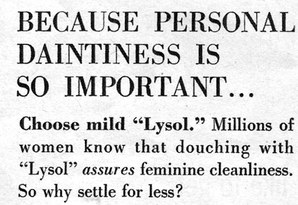

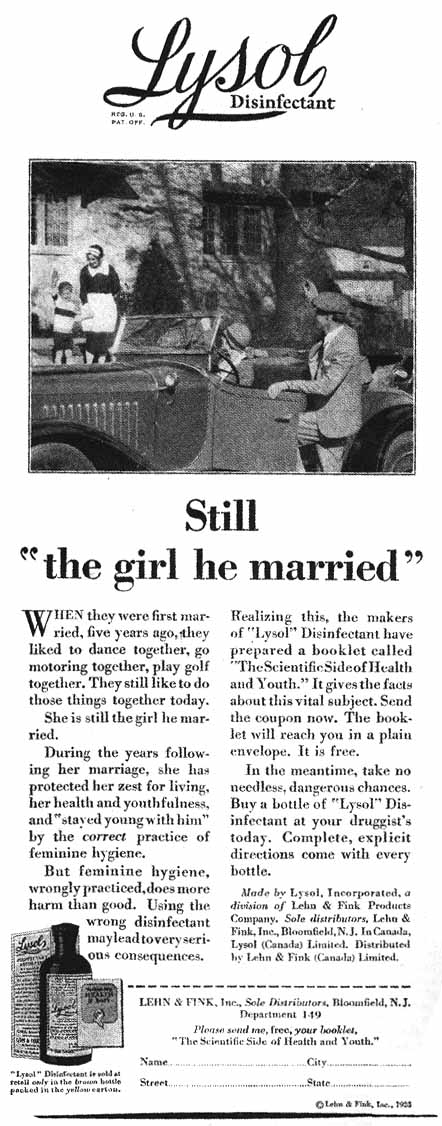

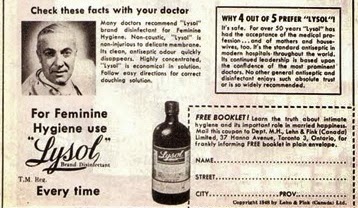

From the 1920s to the 1950s, however, Lysol’s advertising emphasis was less on making the home a safe haven for the family and more on making the vagina a safe haven for the penis. In a series of extraordinary print advertisements, vaginal douching with Lysol was promoted as a necessity for maintaining a heterosexual relationship. In 1928 ‘she’ could be ‘still the girl he married’ because, ‘during the years following her marriage, she has protected her zest for living, her health and youthfulness, and “stayed young with him”’ by using Lysol as a douche; in another ad, from 1934, one ‘Dr Helene Stourzh’ reassures a woman ignorant of ‘the proper method of marriage hygiene’ that using Lysol in the ‘hidden folds of the feminine membranes’ will establish ‘a sense of confidence and trust that turns wretched marriages into happy ones’. (i)

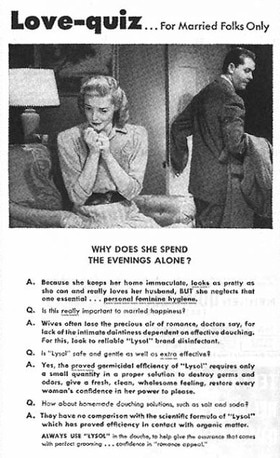

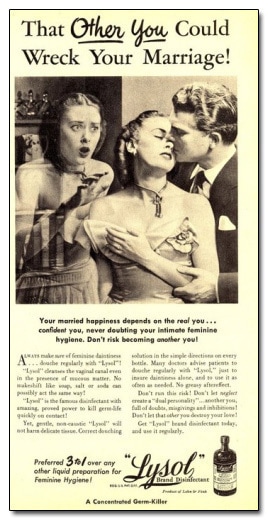

As late as 1948, ‘Married Folks Only’ were invited, in a Lysol advertisement, to take a ‘Love-quiz’. A picture shows a distraught woman, hands clasped tightly under her chin, turning away from her husband who, coat over arm, is walking out of the door. ‘Why does she spend the evenings alone?’ asks the ad. Her ‘crime’ is that she ‘neglects that one essential . . . personal feminine hygiene’; here, indeed, is the ‘shameful’ pudendum. (You’re forgiven if you made the understandable assumption that her ‘crime’ was, in fact, marrying an utterly ignorant tosser.) In another ad from the same year, Lysol helps a wife to ‘hold her lovable charm’, and, in the 1950s, you’re waned that ‘the other you’ (the one who doesn’t regularly spray caustic disinfectant into her vagina) ‘could wreck your marriage’.

Actually, your marriage was far more likely to be ‘wrecked’ when the potentially harmful effects of Lysol’s ingredients were taken into consideration: ‘cresol (a distillate of coal and wood), or mercury chloride, either of which, when used in too high a concentration, caused severe inflammation, burning, and even death’.(ii) Lysol’s efficacy as both marriage-saver and contraceptive was, happily, utterly invalidated in the 1960s, but the idea propagated by the manufacturers, that the vagina is somehow not ‘good’ enough in and of itself, still obtains.

Procter and Gamble, like Reckitt Benckiser, was founded in the early nineteenth century. They now operate in 80 countries worldwide and their 2016 sales figures were a whopping $65.3 billion (around £52 billion). Procter and Gamble want year-round, life-long consumers, hence their dogged emphasis on the ever-imminent ‘odour’ of what, some decades earlier, Lysol had warned women could be a marriage wrecker. Time, then, to ‘Stay fresh as a daisy throughout your day with ALWAYS Dailies Fresh & Protect Normal Panty Liners. With Odour Neutralising Technology’. Every day, since, as the website reads, sounding troublingly like some kind of menstrual random word generator: ‘Vaginal discharge icky but amazing. Vaginal discharge may seem weird’.

For a western woman’s entire life, if she menstruates, or if she does not, her body is a moneymaking machine for the big businesses who set out to cultivate precisely the same fears that Lysol cynically encouraged in the early- to mid-twentieth century. The vagina is sold back to women as an incommodious house-guest; the independent, unpredictable, always-nearly-malodorous enemy within. Lysol has been a household disinfectant and not a vaginal douche (far more a North American phenomenon than a British one anyhow) for decades now, but the fears it traded on are still prevalent. If all women – from the schoolgirls targeted from menarche to have a fear of ‘odour’, to post-menopausal women taught to fear ‘dryness’ and ‘irritation’ – really came to love their cunts, then what would happen to the massive sales figures of these companies? The products – unlike the women they’re targeted at – seriously stink.

i) These adverts from 1928 and 1934 appeared first in the United States in McCall’s magazine. Reproductions of the print adverts can be found at the online ‘Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health’, www.mum.org

ii) Andrea Tone, ‘Contraceptive Consumers’, in Elizabeth Reis (ed.), American Sexual Histories (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), pp. 247–69 (252).

1 Comment

Dan

7/19/2020 07:24:12 pm

I think it's quiet comical, you see when I was a young man I dated many women and some of them stank like a dead animal . dirty vagina s .they sure could have used some Lysol or bleach lol in their douche s.lol

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed