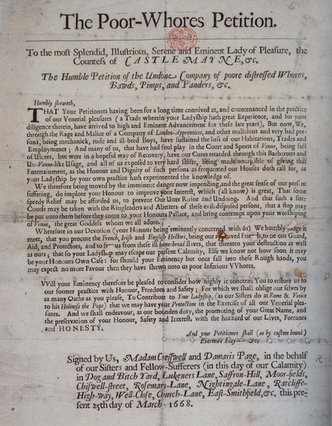

Rebecca Rideal is a writer, historian and former specialist factual TV producer, whose TV credits include Adventurers’ Guide to Britain, Bloody Tales of the Tower, and the triple Emmy award winning series David Attenborough’s First Life. She runs the online history magazine, The History Vault, and is currently studying for her PhD on Restoration London at UCL. Her first book 1666: Plague, War and Hellfire is published by John Murray and out in paperback on 23rd February 2017. You can follow her at @RebeccaRideal  Charles II painted by Philippe de Champaigne, c. 1653 Charles II painted by Philippe de Champaigne, c. 1653 Adapted from '1666: Plague, War and Hellfire'. In June 1665, Charles II was a king in his prime. At the age of 36, he was five years into his restored reign, virile and interested, he was married to Catherine of Braganza, had a pack of illegitimate offspring, a couple of mistresses, healthy heirs in the shape of his younger brother, nephews and nieces, and his prized navy had just defeated the Dutch in the much-celebrated Battle of Lowestoft. There was just one problem – after a thirty-year absence, an epidemic of plague had broken out in the capital. At first, it seemed to be confined to a handful of cases in the outer parishes of the city. By June, however, the weekly Bills of Mortality revealed the number of plague dead across the city to have passed a hundred. Along with his court and a handful of hangers-on (actors, actresses, artists, playwrights and the like), the king fled London to find refuge in Salisbury and then Oxford. Away from London, the threat of plague and an ongoing war did little to curb the licentious behaviour of the court. In fact, if anything, the unfamiliar setting of Oxford threw the court’s frisky and frivolous activities into sharp relief. Describing Oxford during this time, a French servant named Denis de Repas found a place of jollity and extravagance, writing: ‘There is no other plague here but the infection of love; no other discourse but of ballets, danse and fine clouse [clothes]; no other emulation but who shall look the handsomere . . . none other fight than for “I am yours” . . .’ He even came across a rumour that a proclamation was to be ordered forcing everyone to be cheerful or they would suffer the pillory. Yet it wasn’t all sweetness and roses.  Frances Stewart, Duchess of Richmond Frances Stewart, Duchess of Richmond During their stay, a fierce rivalry broke out between the king and his brother, the hot-tempered Duke of York, over a beautiful court ingénue named Frances Stewart – described by their sister as the ‘prettiest girl in all the world and the most fitted to adorn a court’. The king was infatuated and visited her chamber every morning before breakfast. The duke was also enamoured. Confiding to Samuel Pepys ‘as an infinite secret’, the duke’s secretary revealed that ‘factions are high between the King and the Duke, and all the Court are in an uproare with their loose amours; the Duke of Yorke being in love desperately with Mrs. Stewart’. Stewart (who the following year would pose as the Britannia we see on British coinage) refused them both.  The Whores' Petition (also known as The Poor Whores' Petition) was a satirical letter addressed from brothel owners and sex workers affected by the Bawdy House Riots of 1668, to Lady Castlemaine, lover of King Charles II of England The Whores' Petition (also known as The Poor Whores' Petition) was a satirical letter addressed from brothel owners and sex workers affected by the Bawdy House Riots of 1668, to Lady Castlemaine, lover of King Charles II of England The royal wives also set tongues wagging. Queen Catherine’s newly appointed Master of Horse was the narcissistic Ralph Montagu, described as a man who ‘doth both admire and Love himself’. The appointment might have been unremarkable had he not been the brother of the recently-deceased previous Master of Horse, Edward Montagu; a man who had been exiled from court after making romantic advances towards the queen. It was also during this time that rumours started to circulate that the Duchess of York had ‘fallen in love with her new Master of the Horse, Mr Harry Sidney’. Described as ‘the handsomest youth of his time’, Sidney was purported to be ‘so much in love with her’ that the ‘Duke for many days did not speak to the Duchesse at all’. Suffering perhaps the most public scandal while residing in Oxford was the king’s long-term mistress, Lady Castlemaine. While she was heavily pregnant with the king’s child she became the focus of a vicious pamphlet campaign. Seemingly organised by university scholars, it climaxed in a note being pinned to the door of her chamber, declaring: ‘The reason why she is not duck’d / Because by Caesar she is fuck’d’ (the ‘Ducking Stool’ was a humiliating punishment for sex workers). It was not the first and certainly not the last time Lady Castlemaine would be publicly likened to a prostitute. During the Bawdy House Riots of 1668, she was regularly ‘celebrated’ in print as the chief whore of the kingdom. With their complex rivalries and romances, backstabbing, drinking and politicking, the residents of Oxford found members of court to not only be ‘rude, rough, whoremongers’, but arrogant and physically dirty too. On their departure, the contemporary academic Anthony Wood reflected:

"The greater sort of courtiers were high, proud, insolent and looked upon scholars no more than pedants or pedagogical persons . . . Though they were neat and gay in their apparel, yet they were very nasty and beastly, leaving at their departure their excrements in every corner, in chimneys, studies, coalhouses, cellars."

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed