|

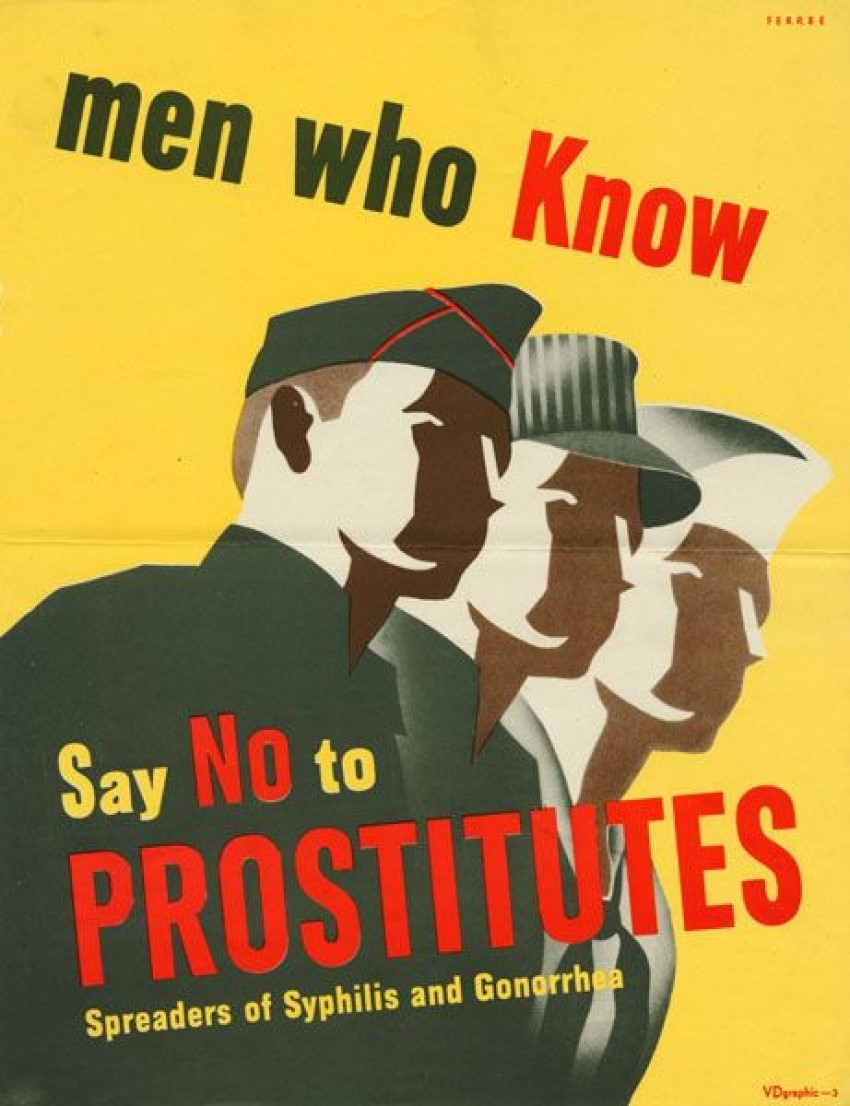

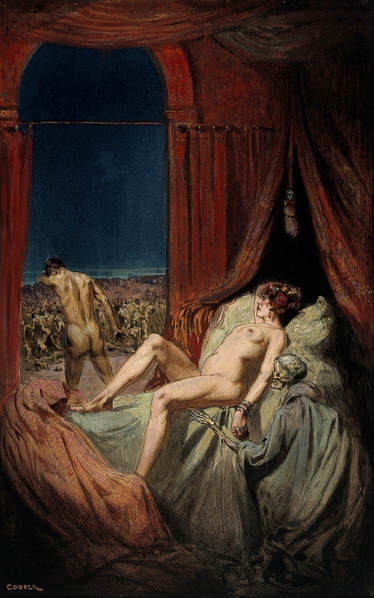

Hester is a HIV/STI surveillance and prevention scientist with a particular interest in syphilis. She developed a interest in both acquired and congenital syphilis though previously studying paleo-epidemiology and the history of medicine at during an MSc in Bioarchaeological and Forensic Anthropology at UCL and then went on to focus on STIs from a more modest stand point through studying Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Syphilis is a disease with many negative social connotations and it has a long and complicated history. Syphilis is caused by the bacteria Treponema pallidum and is most commonly transmitted through sexual contact (Romanowski,1999). Therefore, due to its nature of transmission, there has been a large amount of stigma surrounding this disease throughout its history. In Europe and America, syphilis developed parallel to the process of urbanisation and was linked to increases in promiscuity and prostitution that accompanied the development of densely populated areas (Wood,1978). In parts of the developed world during the 19th and 20th centuries, syphilis was more than just a disease, it developed into a social phenomenon which extended far beyond the field of health alone. The negative societal attitudes towards the disease significantly impacted the treatments used and consequently, exercised a great influence on the prevalence during this period (Quétel,1990). By examining both primary and secondary historical literature concerning the control of syphilis in different countries within Europe and in America from 1840 to 1945, it is possible to gauge the extent of the punitive measures used to control the disease. By understanding the magnitude of the disease and the attitudes towards it during this time, we can scrutinise the justifications of these responses and make assessments of their efficacy. It is important, however that evidence provided by the primary literature is considered within its context, as much of the 19th century writing is characteristically sensationalist (Wiener, 1990). Therefore, these pieces may somewhat portray contemporary social values rather than scientific considerations. Before the discovery of the bacteria that causes syphilis in 1905 and the first effective treatment, Salvarsand in 1908 (Tampa,2014), syphilis was widely believed to be an incurable disease. This belief had a considerable effect on the fear of contagion and fuelled the stigma surrounding the disease at this time (Quétel,1990). Hindsight is not required to recognise the significant effect that syphilis had on society at this time. In 1910 Huici wrote in the American Journal of Public Health that “of all transmissible diseases, syphilis is that which has undoubtedly caused the most ravages among the human race” (Huici,1910). In 1939, Moore, an America psychiatrist claimed that, in comparison with other epidemics such as cholera and tuberculosis, “none of these diseases had caused anything like the conflict and emotional disturbance in the public mind that syphilis has caused”. This period was one associated with increasing moral decline, associated with increasing urbanisation and industrialisation. Hence, many of the responses to syphilis at this time have been considered to part of a ‘moral panic’ (Sauerteig,2001). Moore speculated that the actions taken during the 19th century to tackle the spread of syphilis were perhaps the best ally the disease could have had, suggesting that the control mechanisms used were inadequate and potentially counter-productive (Moore,1939). The historian Sauerteig writes that, during the 19th century syphilis was considered as shameful and was believed to be a punishment or moral condemnation for wickedness and immorality due to its suspected contraction through non-marital sex (Sauerteig,2001). The above statements highlight the hysteria surrounding the disease at this time, a factor that cannot be ignored when considering the reasons for extreme and punitive measures used to control the spread of disease. Much of the literature from the 19th and 20th centuries accentuates the relationship between social class and syphilis. It is frequently suggested that there was a large amount of blame put on the working class for the spread of the disease to the upper and middle classes. In general, syphilis was associated with poverty, low morals and a lack of sanitation (Fildes, 1915). Harsin emphasises how in late 19th century France, heightened fear of contagion from the lower to the upper classes, as well as the widespread belief in contagion through inanimate objects, and disbelief in the reality that even middle class women with "irreproachable morals" (Harsin, 1989) were contracting the disease, generated severe panic surrounding syphilis and this panic was reflected in legislation introduced during this period. These views did not appear to dramatically change throughout this period. In 1937, American physician and editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, Fishbain, concluded that an individual’s chance of infection was dictated by their status within society and occupation. He also stated that the disease was associated with criminals, of whom 20-40% were infected, compared with a mere 2-10% of men from “better families” (Fishbein, 1937). It is clear from this that the moral connotations connected to syphilis were not short lived. In 1938, an American physician, Lock, described the difference in the prevalence in urban and rural areas, stating that within the urban areas there has been a “recent weakening of sex standards” and “sexual behaviour in urban areas are more unconventional” (Locke, 1938), Lock identified the poor working class living in inner cities as carriers of this ‘unsavoury disease’ and linked this to their behaviour. These writings highlight the longstanding associations between syphilis and the lower classes, which can be considered an explanatory factor in understanding the reasons for the punitive measures used to control the spread of this disease. Within Europe during this time period, all regulatory measures to control the transmission of syphilis were aimed at prostitutes and these included the registration of prostitutes, periodic medical examinations and the treatment of infected individuals (Locke, 1938). Although medical confidentiality and the idea of liberal individualism acted not only as a barrier to treatment, but prevented awareness of the disease during the 19th century, in many European cities, the luxury of medical confidentiality was abolished for prostitutes and many working class women (Harsin,1989). When the Contagious Disease Act was introduced in Britain in 1846, the law was thought to be heavily influenced by the increased levels of syphilis the army and navy and therefore was seen as a general threat to the armed forces. This law called for women who were suspected of prostitution, living in garrison towns, to be submitted for internal examinations and if found to be infected with syphilis, were forcefully isolated(Baldwin,1999). Subsequent acts under this name were introduced in 1864, 1866, 1868 and 1869 and the regulations were successively extended beyond just military towns. In Germany, a provision of the German criminal code was introduced in 1872, allowing prostitution only if under police control. Within this legislation, prostitutes were required to register and submit themselves for regular medical inspection by vice squads. In 1900, an imperial act ordered the compulsory notification of the sexual partners of those with syphilis and stated that the deliberate and wilful communication of an infectious disease would be considered assault. In 1927 an act that replaced the legal control of prostitutes with medical control was introduced (Sauerteig, 2001). This act required everyone infected with venereal disease to undergo treatment and those who failed to comply with this treatment were reported to the authorities, which resulted in forced treatment, enforced by the police. In the USA, a system of legalised prostitution was introduced in 1863. Prostitutes were licenced and subjected to weekly examinations, with those diagnosed with syphilis admitted to hospital for free treatment (Parascandola,2008). Subsequently, these attempts at licencing prostitutes were deemed unsuccessful due to the increase in clandestine prostitution that followed the introduction of the regulatory system and the closing of the red light districts. In 1917 the Commission on Training Camp Actives, was introduced to assist the control of venereal disease (Storch,2017), shortly followed by the creation of detention houses and reformatories (Parascandola,2008). Few pieces of literature from this period shed a positive light on prostitution. Some appear to take a harsher view than others and in the early literature there appears to be a general consensus that prostitution was a major causes, if not the prime cause of the spread of syphilis. In his 1862 article on prostitution in London, Hemyng refers to prostitutes as “nothing better than a paid murderess, committing crime with impunity” (Hemyng,1862). In 1859, Miller projected another extremist view of the dangers of prostitution. He describes prostitution as “a multitudinous Amazonian arm the devil keeps in constant field service, for advancing his own ends” and characterises it as a “monstrous evil, terrible in extent, and hideous of mein”. He criticises the lack of legal action against prostitution during this time and attributes this to spread of syphilis, stating that “the slackness of our civic rule in permitting prostitution, brazen faced and open handed, to prowl upon our streets for prey” (Miller,1859). These sources indicate that during this time, some held the view that prostitution was amplifying the spread of syphilis and that prostitution needed to be controlled if the spread of the disease was to be halted. The literature suggests that policy makers and doctors were divided at this time regarding the proposed registration, isolation and forced treatment of prostitutes. These individuals could be divided into moralists and pragmatists. The moralistic approach supported emphasising the dangers of venereal disease and purposefully amplifying the fear surrounding it in order to enforce moralistic sexual self-control (Sauerteig,2001). In 1910, Huici described this group as those who advocate the enactment of regulation, “concentrating on morality and health and therefore brining that vice under regulation” (Huici,1910). This group of people were regarded as holding morality above the health of individuals, and advocated the punitive measures used against prostitutes (Sauerteig,2001). The pragmatists, or those who believe in a more medical approach to the cessation of syphilis (Huici,1910), were described as abolitionists, who concentrated on individual liberty and defended the free exercise of prostitutes. Despite two clear points of view, the legislation that was passed, suggested that, during this period, the moralists prevailed. In 1906 American physician Cumston wrote “of all the diseases that may affect the human race by contagion…there is not one more serious, more dangerous or more feared than syphilis” (Cumston,1906). He went on to express that “the only way to control the transmission of syphilis is to sterilize prostitution as we would sterilize our dressing for a surgical operation” (Cumston,1906). This extreme statement suggests there was a demand for extreme action to tackle the spread of syphilis. It appears that the hysteria and fear surrounding the disease acted somewhat as a justification for the extreme and punitive methods used. Literature on prostitution during the 19th and 20th centuries highlights the inequalities between men and women, as well as the class divisions. This is exhibited by the writings of Huici, who, in 1910, encouraged the isolation of women with syphilis, specifically “the public women who constitute the most abundant and fruitful source of those dreadful diseases” (Huici,1910). He regarded the different social conditions of the men and women as necessitating alternative methods of treatment. According to Huici, the measures applied to women would be unacceptable for men, as “the man is the one who maintains the family and therefore requires to work for that purpose, and it would not be fair to deprive him of the means of furnishing that sustenance by confining him in a place where he could not work”(Huici,1910). This demonstrates a clear flaw in the methods used to control syphilis at this time, as well as the attitudes towards women, as isolating only women would not cease the spread of the infection. It appears that this method was justified because it was considered impossible to inflict these measures on men. As there was a lack of women’s rights at this time, it would have been much easier and, potentially considered more effective, to enforce treatment on women alone, rather than force treatment on neither sex. In 1906 Cumston illustrated the attitudes towards women at this time and concluded that women alone were to blame for the spread of syphilis. He justifies this by stating that a man contracts the disease from a female and “from the very fact that she entered into relations with him, this female leads an active genital life”, if the man were then to pass the disease to another women through her entering into relations with him, through doing so, this woman also “leads a genital life” (Cumston,1906). This highlights the contemporary view that women entering into sexual relationships were considered very differently to men doing the same, and it was more acceptable for men to have sex outside of marriage than women. With no grounding in biological arguments of how the disease is spread, this extract emphasises the moral connotations of syphilis and it appears the author is indicating that the immorality of the women involved in the sexual activity is to blame for the transmission of the disease. In 1840 Tait wrote that “men are, in general, possessed of greater mental power and activity than females; but that is why they ought to extend towards the latter that sympathy and protection to which they are entitled in virtue of their weak and unprotected condition” (Tait,1940). This reveals how justifications were formed for the difference of treatment for men and women, following the logic that women were considered to be weak and therefore needed protection. This attitude is clearly not extended to all women, but only to those within the upper and middle classes. If an upper class woman were to contract syphilis, there was a very different response to that of a working class woman. In 1905 Bukley emphasises the extent to which syphilis was ‘innocently acquired’ and wrote that “wives suffer very frequently from the sins their husbands committed before and during marriage” (Bulkey,1905). In France, in contrast to the treatment of prostitutes, middle class women, due to their assumed purity, were likely to be inadequately treated. At this time, due to laws of confidentiality and the fact that women communicated with physicians through the means of their husbands, the man had the right to control the knowledge that the woman would receive and it was often thought better for matrimonial harmony to keep the women in a state of ignorance (Harsin,1989). Consequently, she was protected from the knowledge of her diagnosis, but not from its effects. The momentous fear and hysteria surrounding syphilis during the 19th and 20th centuries is thought to be a considerable factor for the extreme measures used to control it. It could be concluded that a justification for the extreme treatment of prostitution was an attempt to diminish public hysteria, and with public hysteria being so amplified at the time, extreme measures were needed. Bulkley’s 1905 text supports this through his argument that the sinful connotations and association of the disease with unlawful sexual intercourse would inevitably lead to legal action “once the public is thoroughly convinced that there is a danger that must be avoided”. Nonetheless, he was of the opinion that despite these measures “no intelligent attempt to restrict its ravages” (Bulkley,1905) was made at the time. In Huici’s 1910 article he recognised that prostitution could be used as a means of a woman providing for her own subsistence and therefore suggests a method of isolating prostitutes and giving them a means to live as a method of preventing them from passing on the infection to clients. He speculated that if the prostitute was not to be isolated, treated and given means to live, “she will do her best to attract a greater number of visitors, who will become victims to the disease” (Huici,1910). He stresses that compulsory treatment and isolation is the only way for syphilis to be stopped from being passed on, and questioned whether “supposing that a woman recognised that she was a contaminated.. would she be endowed with such good sentiments as to abstain of her own free will from that intercourse?” (Huici,1910). This emphasises the view that prostitutes are not to be trusted and force would be the only way to gain their compliance with treatment. When questioned on the effects that his proposed actions would have on the rights of individual liberty of prostitutes, Huici responds: “dealing with an evil of such transcendent importance, we must sacrifice certain rights and set aside all sense of pity, when dealing with persons who fully understand their abject condition, know that they are acting contrary to the moral laws, and that by the very reason of their shameful trade, find themselves unable to claim rights which they are unworthy to enjoy” (Huici,1910). This highlights the low regard for prostitutes and suggests that, at this time, it was assumed that prostitution was a choice made by women and they were fully aware of the dangers of the diseases they were carrying. This quote also demonstrates the muddling of moral laws and criminal laws, suggesting that official legal consequences should be given to moral sins. Huici also justifies the harsh treatment of prostitutes by stating that previous methods to regulate prostitution in Belgium, France and Germany were successful in decreasing syphilis by a considerable amount (Huici,1910). Interestingly, a previous article written on the suppression of syphilis in the Journal of the American medical association in 1891 stated that the measures used in Europe with regard to the regulation of prostitution has “proven unavailing from both a moral and sanitary stand point” and that using a system of legal recognition and regulation has proven to be a complete failure (The journal of American Medical Association,1891). This lack of clarity surrounding the effectiveness of these punitive measures suggests that methods may have been used as a vehicle for social purification and the minimisation of immorality, rather than purely a method to prevent transmission. Huici states that the need for establishing a set of regulations for the control of prostitution is also to “defend ourselves at the same time from that other social plague which increasingly propagates moral deterioration” (Huici,1910). Huici recognised, however, that is would be impossible to subject every woman who lives by prostitution to these regulations. He countered this by stating that one would have to be “satisfied with the decrease in diseases ravages and apply those measures in those cases which are within our power” (Huici,1910). Conceding inevitable limitations in these methods, Huici seems to advocate a 'something is better than nothing' approach. This idea is supported by the extreme views posed by Miller in 1859 who rejects the idea that prostitution is an ‘inevitable evil’ and states that the most extreme treatment is needed to squash “this foul fungus on our social surface” (Miller,1859). He believed the legal registration of prostitution would be a method of formally accepting the practice into society and would therefore advocate this ‘moral sin’. He believed “it is another fallacy, and in no slight degree dangerous, to regard syphilis as the main evil of prostitution” and that “the only true prevention of syphilis is chastity” (Miller,1859). These proclamations suggest that there may have been an alternative agenda to the methods used to control of syphilis held by some at this time. Other aforementioned justifications for these punitive measures lie in the need to protect upper class women from the diseases associated with the lower classes, with an emphasis on the innocent contraction of the disease. In conclusion, the historical evidence assessed can help us to understand the means by which punitive responses to the disease were justified by contemporary social attitudes and that these values were prioritised above individual health and scientific considerations. The class divisions, as well as gender divisions and attitudes towards women were all used as grounds for justification for the actions taken. The connection between what was considered to be morally wrong or legally punishable was very different to attitudes seen now and this would have affected how these methods were justified over time. The effectiveness of these interventions in different areas was used as both a justification for, and a warning against implementation of the punitive methods. And as these methods were widespread across Europe and America, within each country there were specific developments, limitations and objections that would have, in turn influenced their effectiveness. References:

Acton, W. (1870). Prostitution Considered in its Moral, Social and Sanitary Aspects in London and Other Large Cities and Garrison Towns with Proposals for the Control and Prevention of its Attendant Evils. John Churchill and Sons, London. Baldwin, P. (1999). Five: Syphilis between prostitution and promiscuity. Contagion and the State in Europe, 1830–1930. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. pp.596. Bulkley, D. (1905). Syphilis as a disease innocently acquired. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, XLIV.9. pp.681- 684. Carpenter, M. (2010) Health, Medicine, And Society In Victorian England. Praeger, Santa Barbara, California. Cumston, C. (1906). What effective measures are there for eht prevention of the spread of syphilis and the increase of prostitution. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, XLVII.17. pp.1372-1375. Curgenven, J. (1868). The Contagious Diseases Act of 1866, and It’s Extension to the Civil Population of the United Kingdom. Publisher unknown, London Davidson, R. & Hall. L. (2001). Sex, Sin, And Suffering. Routledge, London. Fildes, P. (1915). The Prevalence Of Congenital Syphilis Amongst The Newly Born Of The East End Of London. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27. pp.124-137. Fishbein, M. (1937). Syphilis; The Next Great Plague To Go. David McKay Company Philadelphia. pp.15-57 Goodman, H. (1919) Prostitution and community syphilis.. American Journal of Public Health, 9.7. pp.515-520. Harsin, J. (1989). Syphilis, Wives, And Physicians: Medical Ethics And The Family In Late Nineteenth-Century France. French Historical Studies, 16.1. pp.72-95. Hazen, H. (1942) Syphilis In The Negro. Publisher unknown, Washington. pp.1-2 Hemyng, B. (1862). ‘Prostitution in London’ in Mayhew, H., London Labour and the London Poor: Volume IV- Those Who Will Not Work; Comprising Prostitutes, Thieves, Swindlers and Beggars, Dover Publications, New York. Huici, J. (1910). The Necessity of Isolating Prostitutes Who Suffer from Syphilis. American journal of public hygiene, 20. pp.523-530. Locke, H. (1938). Social Aspects Of Syphilis. Indiana State Board of Health, Indiana. pp.7-13. Miller, J. (1859). Prostitution Considered In Relation To Its Cause And Cure. Sutherland and Knox, Edinburgh. Pp.5-30 Moore, M. (1939). Syphilis and public opinion. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology, 39.5. pp.836-843. Parascandola, J. (2008). Sex, Sin, And Science. Praeger, Westport. pp.3-59. Quétel, C. (1990) History Of Syphilis. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. pp.3-115 Romanowski, B & Singh, A. (1999). Syphilis: Review with Emphasis on clinical, Epidemiologyical, and some Biological features. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 12. Pp.187-209. Sauerteig, L. (2001) ''The Fatherland is in danger, save the Fatherland!' : venereal disease, sexuality and gender in Imperial and Weimar Germany.', in Sex, sin and suffering : venereal disease and European society since 1870. Routledge, London. pp. 76-92. Storch, H. (2017). "Changing Views About Syphilis And Sex Education Around World War I – History Of Medicine In America. Available from: http://lewiscar.sites.grinnell.edu/HistoryofMedicine/uncategorized/changing-views-about-syphilis-and-sex-education-around-world-war-i/ .[Accessed:8 Feb. 2017]. Tait, W. (1840). Magdalenism: An Inquiry into its Extent, Causes and Consequences of Prostitution in Edinburgh. P. Richard, Edinburgh. Tampa, M et al. (2014). Brief History of Syphilis. Journal of Medicine and Life,7.1. pp. 4–10. (1891). The suppression of Syphilis JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, XVI.8. pp.274. (1910). The Wassermann reaction in prostitutes. Journal of the American Medical Association, LIV.3. pp.210. Wiener, J. (1990). Constructing the Criminal: Culture, Law and Policy in England, 1830-1914. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. pp.21 Wilmer, H. & Wilmer, H. (1945). Corky The Killer. 1st ed. American Social Hygiene Association New York. Wood, C. (1978). Syphilis In Anthropological Perspective. Social Science & Medicine Part B: Medical Anthropology, 12. pp.47-55.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed