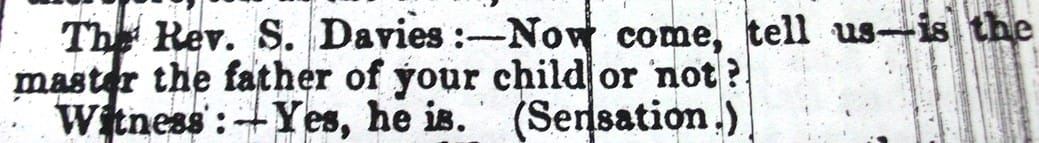

Dr Lesley Hulonce is historian and lecturer of health humanities in the College of Human and Health Sciences at Swansea University. Her research interests include the histories of children, disability, poverty, gender and prostitution via state and voluntary action. Her new book Pauper Children and Poor Law Childhoods in England and Wales 1834-1910 is available here. She is co-director of the Research Group for Health, History and Culture and founder of Academics for a Publishing Revolution. She blogs at Workhouse Tales and Prostitution and Women's Work and tweets at @LesleyHulonce and @HistHealthCult. In 1855, William Prosser the master of Swansea workhouse was investigated for ‘gross immorality’. The local newspaper The Cambrian took a lively interest in the subsequent Board of Guardians meeting in which a female workhouse inmate revealed that he was the father of her child. The extract below shows the reaction of the gathering; a sensation apparently.  It is unclear whether the woman crumbled under interrogation from the Rev. Davies or whether she used the occasion to drop her bombshell. From the evidence given by the other witnesses it doesn't appear to be a coercive coupling, and she did not accuse the master of forcing her. Among the testimony from workhouse inmates and staff, one witness told how she had seen the two engaged in immoral relations in the laundry when the rest of the women were attending the funeral of a fellow inmates child. This demonstrates that not only did workhouse woman stand together in times of tragedy, but the workhouse management were not as punitive as is sometimes supposed. However, Prosser was punished, he was dismissed and ordered to pay maintenance for the child, and although his wife was a popular matron with both Poor Law guardians and inmates, she was also dismissed with some regret, and later gave birth to a stillborn child. It is not difficult to imagine how female workhouse inmates, especially those who had sold sex outside the workhouse, could gain favourable treatment from some less than honorable masters. However, whether this was the intention of Prosser’s paramour remains unknown. Women defined as prostitutes were thought to be morally contagious in the enclosed atmosphere of the workhouse. In 1855 guardians had discussed the ‘evils resulting’ from the system of sick children sharing a ward with prostitutes suffering from venereal and other ‘loathsome diseases’. One visitor was shocked to find a sick female child in the same bed as a ‘well known prostitute’. It was considered that this state of affairs could only lead to the girls in the workhouse becoming prostitutes themselves.[1] However, there were as many examples of inappropriate staff behaviour as inmates. In December 1861 workhouse nurse Mary Thomas, Margaret Hoskins, the cook and Ann Williams the industrial teacher were accused of being incapable of discharging their respective duties from because they were so drunk. They admitted it and it as it was not their first offence all were dismissed and ordered to leave the workhouse immediately. Furthermore, Margaret Hoskins (the cook) alleged gross misconduct by Master Robert Clark And Clark also resigned and acknowledged his ‘improper intimacy’ with her.[2] Although enforced gender segregation would have precluded many sexual interaction between inmates, the ‘Indoor Pauper’ noted in 1885 that flirtations and ‘elopements’ were not uncommon among workhouse inmates.[3] Indeed, Mary Ann Randell was found shut in one of the lavatories with William Jeremiah. Randall was punished by a reduction in diet and six hours in the refractory cell and, while Jeremiah’s diet was also reduced, he was locked up for ten hours in the refractory cell. One assumes it was not the same cell. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Workhouse Sex and the single (workhouse) girl In 1863, passers by outside Swansea Workhouse were treated to the spectacle of inmates Harriet Nichols and Mary Rees leaning out of a window, drunk and half naked. The workhouse master recorded that the women had been dancing around the bedroom late at night, singing obscene songs and annoying the other inmates. As the workhouse matron later testified in court, this culminated in ‘exposing their persons at the windows in a state of nudity’ for which Harriet was sentenced to 42 days hard labour and Mary 14 days.[4] The headline in The Cambrian newspaper was ‘A Caution to Refractory Paupers’, but Harriet Nichols did not appear to be cautioned. She returned to court in 1866 charged with using obscene language, 1867 for drunk and disorderly, and 1871 for fighting with another women in Swansea’s notorious area for prostitution and thievery Regents Court. Andrew Davies claims that there was no contemporary ‘stereotype’ to draw upon for violent, working-class young women, although he points to aggressive or disorderly women being perceived as lacking in ‘womanly’ qualities and subsequently regarded as ‘fallen’ women or prostitutes.[5] Were sexual practices were ‘key markers’ of the status of some women and girls?[6] Many workhouse offences of a sexual nature appeared to be all-female bawdy singing and dancing rather than sexual contact between men and women, although it is of course unknown what encounters remained undiscovered. In Ireland however, although women rioted and bullied other inmates, their actions were more politicised. Anna Clark claims that they used violence to protest against their treatment and also fought each other and bullied quieter inmates.[7] Women always made up a large proportion of poor law recipients; in 1847, 69% of all adult paupers were women.[8] Although many of these female paupers received poor relief in their own homes, women and children were a significant presence in workhouses and, as Geoffrey Pearson demonstrated, working-class girls and young women could be violent and disruptive.[9] In the City of London Poor Law Union, a relieving officer had to be rescued by the police from being beaten by ten young women who had applied to him for food and clothes, and took exception to be offered a bed for the night in the workhouse instead.[10] As David Green claims, in London workhouses, young female paupers rioted and 'generally misconducted themselves' by leaving the workhouse ‘at will’, and fighting with each other.[11] Are these actions of resistance or drunken high spirits? It was not uncommon for alcohol to be smuggled into workhouses, and some inmates often escaped ‘over the wall’ for a night on the town, and records mention that women sometimes returned with money in their pockets. They would endeavour to come back in the same way before morning, but were often caught and punished. Workhouse inmates did not have to accept any punishment, they were free to leave the workhouse. Of course many women with young children could not afford to, but some resisted the system. Elizabeth Stratton had scaled the walls of the workhouse with several other women on Christmas Day, and while the others crept back during the night, Stratton returned the following morning and subsequently took her children out of the workhouse.[12] The workhouse and mothers of illegitimate children Evidence suggests that women with illegitimate children were humiliated in the Victorian workhouse. Indeed, management were keen to make an example of ‘unchaste’ women by reducing their food allowance or making them wear clothes that would mark them out. However the Poor Law Commissioners in London issued a statement in 1839 outlawing this practice.[13] This ruling did not appear to deter some local Poor Law unions, as in 1850 poor law guardians discussed whether ‘a certain class of Females’ should be made to wear a special badge and given a diet of ‘inferior description’. These women had been admitted into the workhouse from ‘profligate habits’ were either pregnant or had borne two or more children, which led the guardians to believe that they were not deterred by the threat of the workhouse. Indeed, many women appeared to use the workhouse as a free maternity hospital, and while they may have been denigrated for their behavior, they did have access to shelter, food and medical care. The Poor Law Commission did not agree with these practices, this was not because of any tolerance towards unmarried mothers. Rather, the 1834 poor law amendment act had declared via the infamous ‘bastardy clauses’ that a ‘bastard should be what Providence had ordained that it should be – a burthen (sic) on its mother’, and ‘placed such conduct in the class of crimes and simply left the mother with the consequences of vice’. So the Commissioners felt that the woman, by her own ‘imprudence’, had been punished by bearing this ‘burthen’ alone and it ‘ought not to affect her treatment in the workhouse’. It is worth mentioning an extract from the Inquiry into the Rebecca Riots in Wales in 1844. One witness related how these ‘bastardy clauses’ in the poor law amendment act affected women when one of his female employees told him: ‘it is a bad time for the girls, Sir, the boys have their own way’.[14] This law allowed men freedom to impregnate girls without fear of future ‘affiliation’ claims. In 1844, the law was changed to allow unmarried mothers to apply to magistrates for affiliation orders which if paternity was proved, the putative father would be obliged to maintain the child financially. For those women who were unable to prove paternity, the alleged ‘promiscuous atmosphere’ of the workhouse might be their only option. [1] The Cambrian, 25 May 1855. [2] The Cambrian, 19 May 1861. [3] Anon., Indoor Paupers, by ‘ONE OF THEM’, 1885. [4] The Cambrian, 19 June 1863. [5] Andrew Davies, ‘“These viragoes are no less cruel than the lads”, Young Women, Gangs and Violence in Late-Victorian Manchester and Salford’, British Journal of Criminology, 39:1 (1999), 72-89. [6] Barbara Littlewood, Linda Mahood, ‘The “Vicious” Girl and the “Street-Corner” Boy - Sexuality and the Gendered Delinquent in the Scottish Child-Saving Movement, 1850-1940’, Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 4 (1994), 549-78, 557. [7] Anna Clark, ‘Wild Workhouse Girls and the Liberal Imperial State in Mid-Nineteenth Century Ireland’, Journal of Social History, vol. 39, no. 2 (2005), 389-409 and Ciara Breathnach, ‘Even “Wilder Workhouse Girls”: The Problem of Institutionalisation among Irish Immigrants to New Zealand 1874’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol. 39, no. 5 (2011), 771-94. [8]Pat Thane, ‘Women and the Poor Law in Victorian and Edwardian England’, History Workshop Journal, vol. 6 (1978), 29-51; Steven King, Poverty and Welfare in England 1700–1850: A Regional Perspective (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2000), [9] Geoffrey Pearson, Hooligan: A History of Respectable Fears (London: Macmillan, 1983). [10] Andrea Tanner, ‘The Casual Poor and the City of London Poor Law Union, 1837-1869’, The Historical Journal, 42:1 (1999), 183-206, 197. [11] David Green, ‘Pauper protest: power and resistance in early nineteenth-century London workhouses’, Social History31 (2006) which [12] Punishment Book, 25 December 1863. [13] Appendix to Sixth Annual Report of the Poor Law Commissioners, 1840, cmd. 253, 56. [14] Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry for South Wales, 1844, cmd. 531, 177.

1 Comment

|

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed