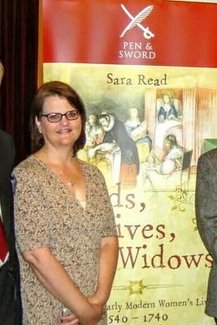

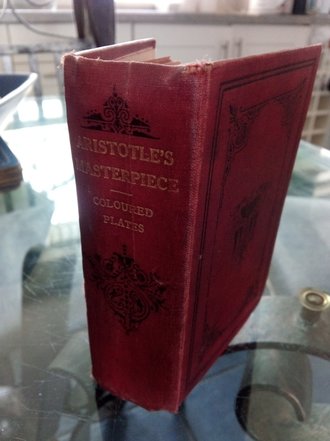

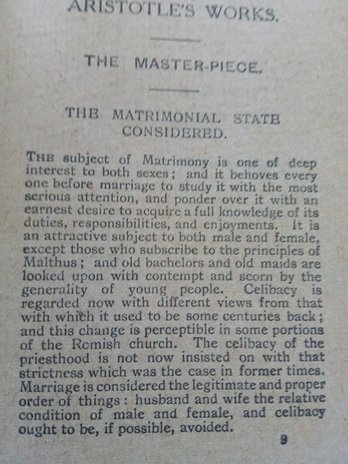

Sara Read is a lecturer in English at Loughborough University and has published widely on the topic of reproduction and seventeenth century literature. In 2015 she brought out a book Maids, Wives, Widows: Exploring Early Modern Women’s Lives with Pen and Sword. Details available http://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/Maids-Wives-Widows-Hardback/p/10534 For more fascinating posts like this one, pop over to the blog she co-edits, earlymodernmedicine.com You can follow her at @saralread  In 1684 a book was published anonymously, called Aristoteles Master-piece, or, The secrets of Generation Displayed in all the Parts thereof. The book was meant to carry the authority of the great Greek thinker Aristotle (b. around 384 BCE). It also carried some sensational images of ‘monsters’ and other phenomena, such as the hairy woman in the image below. It opened with this image to catch the readers’ attention from the start. The book had lofty aims and began the introduction by referring to the Biblical book of Genesis and the Creation. It claimed that it wanted to explain the whole matter of reproduction to its readers, because God ordered it so that humans got pleasure from copulation in order that they would keep doing it and mankind wouldn’t die out:  [God] added Allurements, and desire of mutual embracing, that so they might in procreation be sweetly affected, and pacified by wonderous ways, for unless this was natural to all kind of Creatures, they would be regardless of Posterity, and procreation would cease, whereby mankind would quickly be lost, and the Affairs of mortals of no durance. But that this passionate desire might strongly operate, as well in sensual felicity as on the imagination.[1] Marriage was ordained by God, the author wrote, as a way of expressing these natural feelings in a lawful way: ‘he has thought it convenient to prescribe [mankind] bounds, in granting him the use of the Matrimonial Bed, that so they might not defile themselves’. The introduction ends with a warning that its aim in describing the human body and sex was to be helpful to the readers, but that the author did not desire that ‘this Book should fall into the hands of any obscene Person, whose Folly or Malice may turn that into Ridicule that loudly proclaims the infinite Wisdom of an omnipotent Creator, who by his mighty working is able to subdue all things to himself’.[2] As this warning suggests, giving mankind sexual desire could be dangerous if it led people to sin – and the author wanted to disassociate himself from any notion that his book could be considered what we might refer to as soft porn! Throughout, though, the book was keen to emphasise the pleasures of marital sex. The version of the hairy woman picture used here is taken from a later version of this book, published in 1749, which is something like the twelfth edition of the book in sixty years, which gives an indication of how very popular this book was. In fact, versions of this book were still being published into the twentieth century and although the image of the hairy woman and black child had disappeared, the sentiments about the naturalness of sexual desire being given a natural outlet in marriage remained (see image of Sara’s late Victorian or early twentieth century edition of Aristotle’s Masterpiece). Indeed the opening to this later edition states that everyone considering marriage had an obligation to consider the ‘duties, responsibilities, and enjoyments’ marriage will bring. ** But while the power of the imagination to incline people to have sex with one another was God-given, natural and (within marriage) to be encouraged, the force of the imagination could be double-edged. Coming back to the image which opens the early editions of this book, it is captioned ‘The Effigies of a Maid all Hairy, and an Infant that was black by the Imagination of their Parents’. This refers to the apparent power of the maternal imagination to shape a child in the womb. Indeed the opening image of the hairy woman and the black child are both examples of this phenomenon. This facility of the mother was well-known and accepted in this era. A description of this power is given in an appendix at the end of the book, when the image is reproduced and glossed. It reads: Damascene reports, that he saw a Maid hairy like a Bear, which had that Deformity by no other cause or occasion than that her Mother earnestly beheld, in the very instant of receiving and conceiving the Seed, the Image of St. John covered with a Camels skin, hanging upon the post of the bed. They say Hippocrates, by this Explication of the Causes, freed a certain Noble Woman from suspicion of Adultery, who being white herself, and her Husband also white, brought forth a Child as black as an Aethiopian, because in Copulation she strongly and continually had in her mind he Picture of the Aethiope. We can see from the descriptions of the two images in the drawing that the idea of the power of the maternal imagination is one which had apparently been passed down by ancient authorities including ‘Hippocrates’ himself.[3] These examples and others like it are widely reproduced in seventeenth-century reproduction and midwifery manuals. Early modern notions about the female imagination and its power to detrimentally effect babies carried over through the centuries. In the later versions of Aristotle’s Masterpiece they still appear.[4] My own version has a Chapter ‘The Vagaries of Nature, in the Births of Monsters’ which begins by saying that the reasons for these birth defects are many and no-one knows the whole reason, but then gives the same story of the winged monster born in Italy in 1512 as the seventeenth and eighteenth century editions do. Intriguingly, the rest of that chapter has been torn out of my edition (See image). Perhaps a twentieth century reader found the idea of blaming the mother’s imagination for a child with a birth defect unpalatable. [1] Anon., Aristoteles Master-piece, or, The secrets of generation displayed in all the parts thereof (London: J. How, 1684), p. 2. [2] Anon., Aristoteles Master-piece, p. 4. [3] There is a whole body of work on the maternal imagination, but for more on this particular example see, Cristina Malcolmson, Studies of Skin Color in the Early Royal Society: Boyle, Cavendish, Swift (Routledge, 2016), p. 159. Malcolmson cites James W. Ballantyne’s 1904 work on these writings who finds no evidence in the Hippocratic corpus to suggest the idea was one in these works. [4] Anon., Aristotle’s Works, Illustrated, Containing The Masterpiece (London, no date), p. 34.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed