|

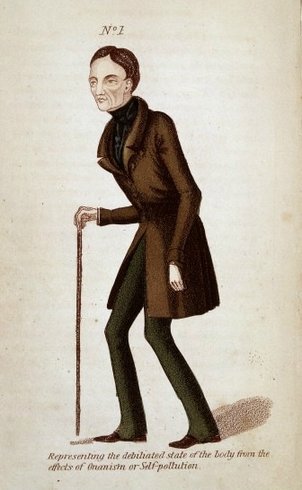

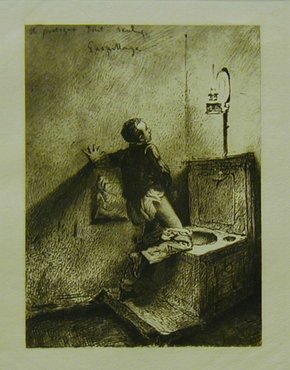

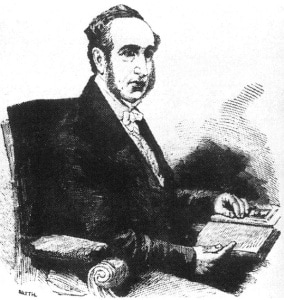

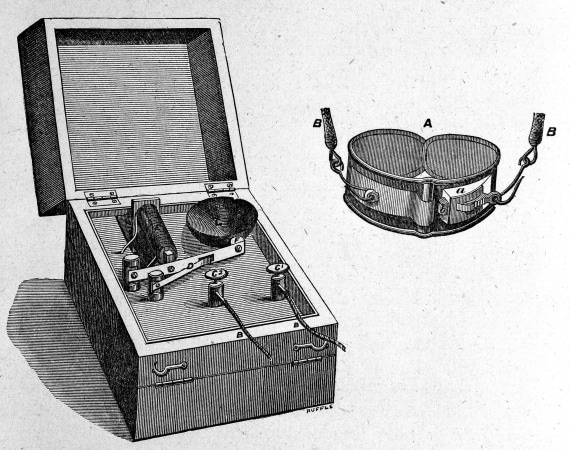

Mimi Matthews researches and writes on all aspects of nineteenth-century history. Her articles have been published on various academic and history sites, including the Victorian Web, and are also syndicated weekly at Bust Magazine, New York. Her first non-fiction book, titled The Pug who Bit Napoleon: Animal Tales of the 18th and 19th Centuries, will be released by Pen and Sword Books (UK) in late 2017. In her other life, Mimi is an attorney with both a Juris Doctor and a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature. She resides in California with her family – which includes an Andalusian dressage horse, a Sheltie, and two Siamese cats. You can follow her at @MimiMatthewsEsq During the Victorian era, masturbation—also known as self-pollution, self-abuse, or onanism—was believed to be both a moral and a physical evil. Medical manuals of the era address it in the most severe terms, blaming male masturbation, and the resulting depletion of the body’s vital humors, for every imaginable illness, from blindness, impotence, and epilepsy to chronic fatigue, mental derangement, and even premature death. Many of these beliefs can be traced back to two 18th century books, the most significant of which was Samuel Tissot’s famous 1760 medical treatise On Onania: or A Treatise upon the Disorders Produced by Masturbation, which asserts: “Frequent emissions of semen relax, weaken, dry, enervate the body, and produce numerous other evils, as apoplexies, lethargies, epilepsies, loss of sight, trembling, paralysis, and all kinds of painful affections.” By the 19th century, concerns about the evil effects of masturbation had risen to epic proportions. The solitary vice was being discussed in medical texts and religious treatises. And the Victorians—who ascribed moral value to self-discipline and restraint—were driven to devise various means of discouraging and controlling it. THE CRIME According to physicians R. and L. Perry in their 1847 book The Silent Friend: A Medical Work on the Disorders Produced by the Dangerous Effects of Onanism: “The practice of the solitary vice, onanism, manustupration or masturbation has been condemned by all writers, whether medical men, philosophers, or divines, from the earliest ages of mankind. One of its names, onanism, is derived from the saddening example of Onan the second son of Judah, who was struck dead by his Creator for the commission of this heinous sin.” The Secret Companion by R J Brodie, 1845. (Image via Wellcome Library, CC By 4.0) In his 1845 book, The Secret Companion: A Medical Work on Onanism or Self-Pollution, consulting surgeon R. J. Brodie calls masturbation a perverted inclination and a baneful habit which “destroys the germ of manhood.” While Dr. William Acton, in his 1894 book on The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs, refers to masturbation as a “melancholy and repulsive habit” that is “degrading and debilitating to the child” and injurious to the adult. Acton advises young men to give up the practice as early as possible, warning them that: “When once the vile habit has become confirmed, the young libertine runs the risk of finding himself, a few years later, but a debauched old man.” Brodie is equally severe. He blames self-abuse on “licentiousness and unrestrained indulgence of the passions,” writing: “Sages and moral writers of every age, have described in glowing terms the direful and awful result of Masturbation a passion that captivates the imagination of its victim imperceptibly, step by step, till every moral feeling is obliterated, and all the physical powers destroyed.” THE CONSEQUENCES According to many moral and medical texts of the Victorian era, not only did masturbation weaken the mind and body, it also weakened the soul. As Brodie explains (quoting M. Hoffman): “We can easily comprehend, how there is so close a connection between the brain and testicles; because these two organs secern from the blood the most subtle and exquisite lympha, which is destined to give strength and motion to the parts, and to assist even the functions of the soul. So it is probable, that too great a dissipation of these liquors may destroy the powers of the soul, and body.”  However, as much as masturbation was considered a moral evil and potential destroyer of one’s soul, the bulk of the consequences resulting from self-abuse were believed to accrue to the body. In an 1843 issue of the Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal, Dr. William Mackenzie, Surgeon-Oculist to Queen Victoria, writes: “…masturbation is often followed by loss of appetite, indigestion, headach[sic], vertigo, tinnitus aurium, rigors, flushings, constant clamminess of the hands, want of sleep, signs of congestion or chronic inflammation of the brain, apoplectic symptoms, palpitation of the heart, and emaciation, leading to a suspicion of phthisis. Palsy and insanity are not unfrequent consequences of masturbation.” In The Secret Companion, Brodie includes several case studies of individuals suffering terribly from the consequences of over-indulgence in the solitary vice. In most of the studies, the patient picked up the habit while still a boy in school. For example, Brodie describes one patient as: “R.I., aged twenty, of slender form, sunken eyes, pallid countenance, and considerable emaciation, stated that when placed at a public school, at the age of twelve, he had been induced by his school-fellows to indulge in the habit of self-pollution…” While in another case, Brodie describes a gentleman of “profound learning” who declared “with the deepest anguish” that: “…the fruits of his academical labours would never compensate for the mischief incurred from a solitary vice taught him by a depraved companion, when he was about thirteen years of age.”  There were many similar cases wherein the patient had learned the particulars of self-abuse from his schoolfellows only to continue the practice as an adult—at which point, the patient’s health inevitably suffered. In one case, Brodie describes a man so affected by the consequences of self-pollution that he “less resembled a living creature than a corpse.” Confined to a straw mattress, where he languished in considerable pain, the patient could do nothing all day but reflect on the evils of masturbation. Brodie writes: “Thus overwhelmed in misery, he languished almost without any assistance for some months, and was the more to be pitied, for what memory he had remaining, and which he was at length entirely bereft of, only served him to take an incessant retrospect of the cause of his misfortunes, which were increased by the aggravating horrors of remorse.” THE CURE According to Brodie, the patient who wished for relief from the consequences of masturbation must first: “…entirely discontinue this dreadful practice, however difficult to do so from the force of habit…” The Electric Alarum for Treatment of Masturbation, 1887. (Image via Wellcome Library CC BY 4.0) This was often easier said than done, especially for those patients who reported engaging in the solitary vice multiple times each day. To aid the process, doctors frequently recommended changes in diet, an increase in physical activity, and prayer. Visualization exercises were also sometimes recommended. For instance, Acton quotes the advice of a clergyman on dealing with unhealthy impulses at night, writing: “[If a] man is tormented by evil thoughts at night. Let him be directed to cross his arms upon his breast, and extend himself as if he were lying in his coffin. Let him endeavor to think of himself as he will be one day stretched in death. If such solemn thoughts do not drive away evil imaginations, let him rise from his bed and lie on the floor.”  For desperate cases, doctors sometimes recommended desperate measures. There were cordials and various patent medicines (Brodie’s medical practice sold Cordial Balm of Zeylanica). There were also more invasive types of “cures” such as spiked rings or electric shock devices for the genitals. According to the book Sexualities in Victorian Britain, by the 1850s some doctors were even beginning to recommend circumcision as a treatment for masturbation. Four Pointed Urethral Ring for the Treatment of Masturbation, 1887. (Image via Wellcome Library CC BY 4.0)  BUT WHAT ABOUT WOMEN?? Most of what was written about the dangers of masturbation in the Victorian era was directed at men. However, women were not entirely exempt. According to author Joan Perkin in her 1993 book Victorian Women, some doctors believed that masturbation caused “increasing numbers of hysterical cases among girls.” While others said that masturbation caused “certain forms of insanity, epilepsy and hysteria in females.” Dr. Isaac Baker Brown, 1851. At its most extreme, the cure for the solitary vice in women was grim. Perkin mentions a gynecologist named Isaac Baker Brown who ran a clinic in London during the 1860s. He called masturbation in women “anti-social behavior” and, as Perkin reports: “His treatment was removal of the clitoris.” Brown was not the only doctor during the Victorian era to perform clitoridectomies on girls and women, but the practice, as a whole, was extremely controversial. Perkin points out that the total number of females operated on “must have been very small.” As a side note, Brown was ultimately expelled from the Obstetrical Society. A FEW FINAL WORDS… Opinions on the physical and moral dangers of the solitary vice did not change rapidly. Even today, there are some for whom the subject is still a controversial one. However, rather than address modern day arguments, I will close this article by taking you back to the 19th century. In his 1872 book on Male Continence, American preacher John Humphrey Noyes addresses masturbation in one particularly hilarious paragraph, writing: “…it is obvious that before marriage men have no lawful method of discharge but masturbation; and after marriage it is as foolish and cruel to expend one’s seed on a wife merely for the sake of getting rid of it, as it would be to fire a gun at one’s best friend merely for the sake of unloading it. If a blunderbuss must be emptied, and the charge cannot be drawn, it is better to fire into the air than to kill somebody with it.” Works Referenced or Cited in this Article Acton, William. The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, 1894. Brodie, R. J. The Secret Companion: A Medical Work on Onanism or Self-Pollution. London: R. J. Brodie & Co., 1845. MacKenzie, William. “On Asthenopia, or Weak-sightedness.” The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. Vol. 60. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1843. Noyes, John Humphrey. Male Continence. Oneida: Oneida Community, 1872. Perkin, Joan. Victorian Women. New York: New York University Press, 1993. Perry, R. The Silent Friend: A Medical Work on the Disorders Produced by the Dangerous Effects of Onanism.. London: R. and L. Perry, 1847. Sexualities in Victorian Britain. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996. Tissot, Samuel Auguste David. A Treatise on the Diseases Produced by Onanism. New York: Collins & Hannay, 1832.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed