|

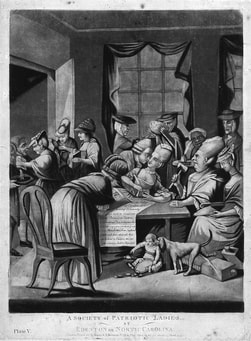

Jan is a cultural anthropologist currently working on a masters thesis about Polish BDSM communities at the Institute of Polish Culture (University of Warsaw). Jan's research focuses on the history and culture of sadism and masochism/BDSM, and by extension history of perversion in Western culture. In 1757, writing on issue of ever-increasing amounts of tea leaf being imported into Britain, English essayist and known eccentric Jonas Hanway claimed that: “I hear near four millions of pounds have paid duties, and if a war takes place, it may amount to five million. Where will this evil stop?” For Hanway, and a cadre of other like-minded polemicists, the surging popularity of the foreign, Chinese infusion was a threat to the nation’s well-being and its future health. However, their efforts to stem the flow were in vain. By the mid-18th century, tea had surpassed coffee as the premier hot beverage in England and was well on its way to establish itself as the quintessential British drink. Even with heavy taxes being imposed on this import, the growth of its popularity did not slow. While the controversy of tea’s impact on the societal health did not really die out until well into the 19th century, Hanway’s view of tea as a danger to the survival of the British people ultimately became a historical curiosity. In the so-called “tea histories”, a genre of texts emerging in the Victorian period with the aim of promoting the benefits of tea-drinking on the individual and the nation alike, Hanway’s dispute with Samuel Johnson on the subject of tea was presented as the forlorn cause of the man best known for introducing umbrellas to London. Of course, “tea histories” tended to be thinly veiled marketing material funded by the tea importers. Their presentation of the British attitude towards tea and tea-drinking was entirely uncritical. However, that is not to say that they were not representative; what they contained was a clear description of the idealized British attitudes towards tea-drinking and its contents. Their tone is difficult to convey without quoting at least a few passages. And so, for example, in J. Sumner’s 1863 A Popular Treatise on Tea we read that: Tea has not yet made much impression upon the Tartars; and the reason may be that it is only the coarser part of the leaves that falls to their share. This is beaten up and moulded into what are called bricks, and in this form sent into the desert. When the Tartars, however, came into China, and drank fine Tea out of porcelain cups—they lost their distinctive character in a very short time, and behaved as if to the manner born. So far from conquering China as is commonly supposed, they yielded to its tea. They annexed their vast territory to the empire, and while nominally reigning, submitted to the governments, laws, and customs of the country— in fact, became Chinese The claim that tea-drinking was crucial in the process of civilization may seem to us an example of rhetorical excess. However, such statements are commonplace throughout the entire genre, and openly link the success of a nation with its consumption of tea. The belief is often presented in an eminently direct fashion, such as in G. G. Sigmond’s Tea, Its Effects Medicinal and Moral: 'A curious, and not an uninstructive, work might be written upon the singular benefits which have accrued to this country from the preference we have given to the beverage obtained from the tea-plant, above all those that might be derived from the rich treasures of the vegetable kingdom. It would prove that our national importance has been intimately connected with it, and that much of our present greatness, and even the happiness of our social system, springs from this unsuspected source. It would show us that our mighty empire in the East, that our maritime superiority, and that our progressive advancement in the arts and the sciences have materially depended upon it. Great, indeed, are the blessings which have been diffused amongst immense masses of mankind by the cultivation of a shrub, whose delicate leaf, passing through a variety of hands, forms an incentive to industry, contributes to health, to national riches, and to domestic happiness. The social tea-table is like the fireside of our country, a national delight; and, if it be the scene of domestic converse and of agreeable relaxation, it should likewise bid us remember that every thing connected with the growth and preparation of this favourite herb should awaken a higher feeling that of admiration, love, and gratitude to Him "who saw every thing that he had made, and behold it was very good.'  Over the span of little more than half a century, tea rose from the position of a novelty drink to one of a national staple that was described as the source of both imperial prosperity and moral superiority. As is often the case, multiple factors contributed to this story of incredible culinary success. For example, widespread smuggling of the tea leaf into England in response to the aforementioned taxes imposed on tea imports in the 18th century likely helped tea spread more evenly across the nation, as the tea-clippers’ captains preferred to avoid major trade hubs such as London and instead tended to offload their cargo in more remote locations. Yet, as much as such factors can help explain the popularity of tea across all social strata of period Britain, they do little to frame how the drink acquired its vaunted position as the centrepiece of Britishness. To provide an answer to that question, however partial, we need to examine a peculiar development that took place over the latter half of the 18th century: the association of tea-drinking with the domestic sphere and – by extension – its gendering as feminine. Rakes and booze To the Victorians, the English people of the 18th century lived lives constantly beset by vice, but 18th-century society was not without its contemporary social critics. The famous series of paintings by W. Hogarth – The Rake’s Progress – documented this anxiety. The titular rake’s journey from riches and high-living to rags and madness led through locales of consumption: public houses, brothels, gambling dens. What those places all had in common is that they represented the dissolution of domesticity and monogamous, heterosexual social bonds. Whoring, drunkenness, gambling; all those vices could be framed as the antithesis of moral, temperate domestic living. The specter of intoxication lingered over all such depictions; it is no surprise that the belief in the moral decadence of the epoch was closely linked with the observed increase in the consumption of spirits. Gin became the symbol of the societal woes rocking England, so much so that it came to be referred to as “the Author of All Sin”. The homosocial environment of public houses, inns and taverns was seen as exemplifying the intemperate, immoral submission to vice which endangered the nation’s health and future, represented by drinks: gin, ale or punch. It was also then that the paths of tea begun first to cross with those of other staple drinks. In the course of the moral panic surrounding the “gin craze”, tea, described in a 1750s pamphlet as “a delicious Nectar” that had “all the good Effects of wine without any of the ill”, started being viewed as a possible replacement for alcohol. To that end, the Gin Act of 1751 encouraged an increase in the amounts of tea being imported (likely to Hanway’s despair.) In that, tea-drinking aligned itself with the idea that British society needed to break away from its old habits and restore its morals, which was gaining traction as the century drew to a close. Motivated by and finding support in the religious revival of that time, it ultimately paved way for what we now describe as “Victorian morality”, which often cast itself in contrast to the indecency and sinfulness of what came before. As the rakes and drunkards of the time drank gin and punch, the revivalists found for themselves a different beverage: tea. Of course, the adoption was not wholesale. In 1749, John Wesley himself had penned a tract titled “A Letter to a Friend Concerning Tea”, where he expressed his concerns with regards to tea’s adverse health effects as well as its nature as a luxury commodity. However, such reservations did not take precedence over the need for a staple drink to contrast with the ones representing sin and vice. In the end, the revivalist sentiment can best be summed up in the verse by William Cowper, a late 18th century poet and a fervent Evangelical, who celebrates tea as “the Cup that Cheers but does not inebriate”. But what does this have to do with women?  A British cartoon satirizing the Edenton Tea Party participants A British cartoon satirizing the Edenton Tea Party participants Fireside of our nation If the moral threat lurking behind the rakish behavior seen in public houses was the destruction of the family life, then it stands to reason that the restoration of the domestic sphere and proper familiar relations was one of the main goals of the late 18th century moral revival. The image of a fraternal group of men gathered around a punch-bowl in an inn, or married men and harlots mingling in a brothel, flagons in hand had to be replaced with something more virtuous. The direction of this change can be seen in J. Highmore’s painting Mr. Oldham and his Friends from 1750. There, we can see a number of men sitting around a punch bowl. It is a common motif, one that was often exploited for satire on immoral, unrestrained behaviour. But here, the atmosphere is different; the men are gathered in a domestic environment. Gone is the rapaciousness of a gambling den or a watering hole. The men are stately, gentlemanly and composed. In other words, civilized and moral. The painting stands at a midpoint: the domestic environment is already there, and it is working its charm. But the drink is still alcohol and the gathered are friends, not family. Therefore something is still missing. The thrust of the idea was that the return from the dens of vice to the sanctity of the fireside would provide the impetus necessary for the man – the husband – to be reunited with his wife and family. Tea was uniquely disposed to facilitate this. Unlike alcoholic drinks, conceptualized as drawing the family away from the sacred fireside, and unlike its other great competitor among warm beverages, coffee, tea, from its very onset in Europe, was a drink primarily prepared and consumed at home. As such, the duty of procuring, keeping track of and properly preparing it fell, along with other kitchen work, to the wife. Even if servants were present, it was still the obligation of the woman, as the house-tender, to oversee the preparation and serving of tea. Therefore, every occasion of it being served simultaneously provided an opportunity for the performance and reaffirmation of the female role of the keeper and the maintainer of the house’s well-being. In this, the context of tea consumption went beyond just domesticity. The public house, or any other example of a site of “intemperate” drinking, was characterized as both being liberated from the constraints of the at-home etiquette and also intensely homosocial, as hinted by a motto adorning a 1759’s punch bowl, calling to “Fill up the Bowl/Let Not our Wife us Control.” Meanwhile, the prime site of tea-drinking – the tea table – could be seen as the diametric opposite. It was, after all, where the family and the house-guests gathered. The relations around it, while often not limited to just one sex, were tempered and moderated by the domestic surroundings and sense of etiquette. It was where the social hierarchies between the husband and the wife, between the masculine and the feminine, were put on a display. The wife, serving tea for the house-guests, was the epitome of proper femininity, and the cross-sex gathering at the tea-table (a gathering that was cheered, but not inebriated) was the prototype of correct modes of social relations.

This display found itself reinforced by and reflected by the accoutrements necessary for proper tea-drinking, porcelain. China, initially imported along with tea (often serving as additional ballast for tea packaging) was inextricably linked with the act of its drinking, so much so that there is evidence suggesting that even the most modest of tea-drinking households sought to have at least some form of porcelain tea service, even if chipped and damaged. At the same time, a similar association existed between femininity and porcelain. The material, characterized by its whiteness, beauty and delicateness seemed to hold the same qualities as the ones that the women were to be endowed with; collecting china sets for the household was a characteristically feminine pursuit. Furthermore, porcelain could also be contextualized within the wider framework of moral revival, as evidenced by Josiah Wedgewood’s heavy involvement in the abolitionist movement, one of the chief examples of a widespread societal sentiment breaking away from the sinful past and motion towards a more virtuous society. This link becomes clearer when we take into consideration that tea and tea-drinking, over the course of the 18th century, became one of the tools at the disposal of the temperance movement. Gaining prominence at the end of the 18th century and seeking to promote sobriety and virtuous living among all social classes (but particularly the lower ones), the temperance movement was heavily involved in both the moral and religious revival tendencies of the time. Creating an opposition between alcohol and tea, the Temperance Movement embraced the warm beverage as one of its staple offerings. In the early 19th century, a “tea party” often served as a synonym for the temperance movement’s public feasting. The link between domesticity and tea was likewise exploited. The temperance movement’s tea parties were heralded as an alternative to the improper, alcohol-fueled gatherings at inns or taverns, seeking to transposition the model of the domestic, cross-sex gathering at the table onto public life at large. The objective was a broader transformation of the patterns of popular pastime activity towards a more virtuous model; for example activities such as dancing were, during tea-parties, replaced with singing religious hymns. The sentiment can be best presented by quoting from a William C. Taylor’s description of a 1840s tea-party held at a factory: 'To the tea-party accordingly we went and found a large room crowded with persons of both sexes all from the mills. [...] Everything went off most orderly; and after the tea-things were cleared away a gentleman [...] addressed the company, not in a condescending manner, but in a way that gave you an idea that they were all friends [...]. The whole affair went off with as little breach of propriety, or even etiquette, as if it had been in a fashionable drawing room; no noise or confusion of any kind.' Tea, women and the middle class It would be mistaken mistake to claim that gin, “The Author of All Sin”, and all the other alcoholic beverages were consumed only by men or only outside homes. However, the 18th century reputation of moral degeneracy, was seen as drawing families apart and dissolving the domestic mirth. The modes of consumption were framed not as economical, but moral. Conversely, it is not possible to say that tea was a woman’s drink, and understood as something feminine. However, the context of its drinking – the domestic sphere – opened it up for the possibility of putting within a larger framework of a domestic and moral revival. Tea existed in the background of religious change, of the temperance movement, of a vision of restored family relations. It is commonly understood that the shift in social mores and the religious revival of the late 18th century led, among its other effects, to the imposition of a distinctly middle-class set of morals as the one standard of behaviour and social relations that is proper and virtuous. The flight away from the figure of the rake helped establish the bourgeoisie not only as the leading economic force, but also the heart of British morals. Tea existed at the crux of all these phenomena, and behind tea there was always a woman. Values ascribed to tea-drinking: moderation, domesticity, and virtue, found themselves reflected through all aspects of its consumption, from the domestic environment of the tea table, the fragile beauty of a china set and finally in the person of the woman serving the beverage at the nation’s fireside. By pouring tea into the husband’s (or guest’s) pot, she was reaffirmed as the household caretaker. Again firmly coded as the domestic, temperate, fragile and beautiful creature, she became at the same time a symbol of the revival’s success – success which was, in many ways, contingent on her serving as the angel in the house. That angel would be serving tea, and tea would be that angel’s duty. Tea was not made feminine in the sense of it being a “drink for women” – no, quite the opposite. It was the drink for the nation. However in the very process of how the drink was prepared, the idea that the woman supports the man – just as the family supports the nation – was both performed and reinforced. Cultural significance of tea-drinking in 18th and 19th century Britain cannot be, of course, simplified just to reinforcing the ascendancy of the new societal mores and the middle class. However, no matter how it is approached – whether as a symbol of prosperity, a commodity in globalising trade, a cog in the system of colonial exploitation or a literary device – it remains attached to the period’s notions of femininity.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Sex History ContentsIf you would like to submit an article, please fill out a submission on the Contact page Archives

September 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed